A lone candle flame quivers in the darkness. You sit in a velvet-draped chamber, heart pounding quietly in your chest. In front of you looms a tall mirror. Its polished surface reflects nothing but blackness behind you. The air is thick with anticipation and a touch of candle smoke. As your eyes adjust, you catch a faint glimmer—was that movement within the glass or just your imagination? Your fingers grip the arms of the chair. In that silent moment, a shape seems to form in the mirror’s depths. An outline, pale and wavering, steps forward…

Such chilling scenarios have been whispered about for centuries. The idea of psychomanteums – mirror-filled chambers used to communicate with spirits – is as old as it is eerie. From ancient Greek temples of necromancy to modern-day paranormal experiments, people across eras and cultures have gazed into reflective surfaces seeking contact with the beyond. This long journey blends history, folklore, and paranormal theory, inviting us to peer into humanity’s eternal desire to reach “the other side.”

So, steel your nerves and settle in. The lights are low, the mirror awaits, and the shadows are stirring. It’s time to enter the psychomanteum and see what secrets the reflections will reveal.

What Is a Psychomanteum?

The word psychomanteum might sound arcane, but its meaning is straightforward. It comes from Greek roots roughly translating to “spirit oracle” or “soul prophecy.” In practice, a psychomanteum is a dedicated space – usually small, dark, and quiet – where a person gazes into a mirror in hopes of making contact with spirits or eliciting visions. Think of it as a cross between a meditation room and a paranormal portal.

Typical modern psychomanteum setups involve a comfortable chair facing a slightly angled mirror. The angle is important: it’s positioned so that you cannot see your own reflection when you sit down. Instead, the mirror shows only the darkness of the room around you (often the wall or ceiling behind you) and eliminates distractions. The chamber is kept very dim; a single low light or candle is placed behind the viewer or off to the side, providing just enough glow that the mirror isn’t completely black. Surrounded by heavy curtains or walls painted dark, the atmosphere becomes womb-like – insulated from outside sound and light. In that stillness, gazing into the depth of the mirror’s darkness, people enter a trance-like state. They may start to see wisps of light, fogginess, or images forming in the mirror. In essence, the psychomanteum is a tool for scrying (a term for gazing into reflective surfaces to receive visions).

But a psychomanteum isn’t merely an invention of modern ghost hunters or New Age mystics. The concept draws on a long lineage of mirror magic and spirit consultation that spans cultures. Before we delve into contemporary experiences – including surprising reports of people seemingly reuniting with lost loved ones – let’s travel back to where this all began. We’ll find that our ancestors, from ancient Greece to Mesoamerica, were no strangers to the idea of peering into reflective depths for glimpses of the unknown.

Ancient Greek Necromancy: The First Mirror to the Dead

To find one of the earliest psychomanteum-like practices, we journey to ancient Greece, over two thousand years ago. Here, the desire to speak with the dead was strong enough to inspire the construction of special oracles dedicated to that purpose. The most famous was the Necromanteion of Ephyra, a temple of necromancy on the banks of the mythical river Acheron, believed to be a gateway to Hades. By torchlight, seekers would descend into underground chambers, hoping to receive counsel from departed souls.

Interior of the ancient Necromanteion, a subterranean chamber where the living sought audience with the dead. Visitors to this Greek oracle would undergo intense rituals before gazing into darkness or reflective surfaces for visions.

The rituals at the Necromanteion were elaborate and designed to induce an altered state. Historical accounts and archaeology give us a glimpse of what transpired there. Visitors might spend days fasting or eating a peculiar diet prescribed by the priests. Ancient writings suggest a ceremonial meal of barley bread, broad beans, pork, and oysters – foods symbolically linked to the underworld. Purification rites were performed to cleanse the seeker spiritually and physically. In the depths of the temple, priests carried oil lamps whose flames cast dancing shadows on stone walls, setting an otherworldly stage.

One especially intriguing detail: a large bronze cauldron filled with water stood in a hallway of the Necromanteion. The inside of this cauldron was polished to a high shine. Under the flicker of lamplight, the water’s surface and the metal’s gleam created a crude but effective mirror. Imagine a weary Greek pilgrim, having fasted and prayed, now led into a long chamber. The air is smoky with incense. He is told to gaze into the still water of the cauldron. Behind him, perhaps unseen, a priest whispers invocations to underworld deities Persephone and Hades. The seeker stares at his own dim reflection in the water, and as minutes stretch on, his eyes lose focus. The reflections of flames ripple across the liquid, and in this hypnotic state he might begin to see something more – the faint figure of his departed wife, or the visage of an ancestor offering guidance.

Ancient Greek literature even gives us specific stories of these ghostly consultations. The epic Odyssey recounts how the hero Odysseus performed a necromantic ritual to speak with the soul of the prophet Tiresias and with his own deceased mother. While Odysseus did not use a mirror (he slaughtered animals and gazed into a pit filled with blood as an offering to attract spirits), the underlying principle was similar: create a liminal space where the living and dead can meet. In Homer’s tale, ghosts gathered, drawn by the sacrifice, and Odysseus beheld and spoke with them – an eerie parallel to later practices of mirror-gazing, where the apparition is coaxed into view.

Herodotus, a Greek historian, tells perhaps the most sensational tale from the Necromanteion. Periander, the tyrant of Corinth in the 6th century BCE, sought advice from his dead wife, Melissa. As the story goes, Periander had hidden a treasure and lost track of it, so he dispatched envoys to the Oracle of the Dead to get answers from Melissa’s spirit. What happened next is truly the stuff of ghostly drama: Melissa’s shade did appear (presumably through whatever visionary method the oracle used – possibly that cauldron of water and bronze). However, she refused to help at first, complaining that she was cold without the clothes that should have been burned for her funeral. To prove her identity to her husband, the ghost revealed a shocking secret that only Melissa could know – a scandalous detail about Periander’s treatment of her corpse. Terrified and convinced, Periander ultimately complied with the spirit’s request by burning vast amounts of clothing as an offering, and only then did Melissa divulge the needed information about the lost treasure.

This lurid anecdote underscores how seriously the ancients took these rituals. Whether or not the details are true, it shows the belief that, in the right setting, the dead could appear and converse with the living. The mirror-like cauldron at Ephyra was key to that setting, acting as a conduit for visions. In essence, those temple chambers functioned as early psychomanteums, complete with all the atmosphere one could ask for – darkness, flickering reflections, chanting priests, and emotionally primed seekers.

Not all Greek mirror magic was so grim, however. Another practice, known as catoptromancy, involved divination using a mirror in other contexts. Pausanias, a traveler and geographer of the 2nd century CE, wrote that at the sanctuary of Demeter in Patras, a mirror could be dangled on a thread into a sacred well. By peering at the mirror’s reflection on the water, a priestess would supposedly receive visions about a sick person’s fate – whether they would recover or perish. Here again we find the motif of a reflective surface (mirror + water) used as a gateway to hidden knowledge, possibly even communication with spirits or deities controlling one’s destiny.

The Greeks, pragmatic yet deeply superstitious, understood one thing: the mind, when given a dim reflection and a hopeful purpose, might just conjure miracles. Whether those miracles were messages from beyond or from the subconscious was, of course, up for interpretation – even then.

Mirrors and Spirits Across Ancient Cultures

The Greeks were far from alone. In the ancient world, many cultures toyed with reflective surfaces as tools for connecting with unseen realms. It seems that as soon as humans saw their faces staring back from a pool of water, we wondered if something else might be staring back, too.

In ancient Egypt, diviners and magicians reportedly used bowls of ink or water for scrying. An Egyptian seer might pour oil into a basin of water to create a dark, shiny surface, then gaze into it until visions appeared. These could be used to answer questions or relay messages from gods and spirits. The practice was akin to using a portable well of darkness – essentially an early psychomanteum on a tabletop. For a civilization that buried mirrors (usually polished copper) in tombs for the deceased to use in the afterlife, the Egyptians held deep associations between reflections and the soul.

Persian Magi and Babylonians similarly gazed into shining surfaces – be it polished metal or liquid – as a means of divination. The idea that an otherworldly truth could reveal itself in a reflection is recorded by writers like Apuleius and later by medieval Arabic scholars. For instance, one technique from the Middle East involved a “magic mirror” where the scryer would paint the mirror’s surface black (often with ink or kohl) and then have a young boy stare into it. The innocence of the child, so the belief went, made him a better conduit for whatever visions might emerge. Tales abound of sorcerers in Babylonian lore who could summon the images of gods or djinn in mirrors and command their knowledge.

Traveling across the ocean to the Americas, we encounter one of the most striking examples of mirror use: the Aztec civilization. The Aztecs crafted circular mirrors out of obsidian – a glossy black volcanic glass. These were not everyday grooming mirrors, but ritual instruments associated with the divine. The very name of one of their most powerful gods, Tezcatlipoca, means “Smoking Mirror.” He was often depicted with an obsidian mirror either on his chest or in place of a foot, and this mirror was said to give off smoke and allow him to see visions of the future (and to spy on people!). Aztec priests and sorcerers used obsidian mirrors for divination and possibly for contacting supernatural beings. Imagine an Aztec shaman in a temple lit by flickering torches, lifting a disk of polished black glass. As he gazes in, chanting and inhaling sacred herbs, he might see the hazy form of a god materialize in the dark sheen, or gain insight into enemy movements or the fate of the harvest. To the Aztecs, these mirrors were true portals – tools that could open onto the realm of gods and spirits.

This tradition intriguingly crossed into European hands in the 16th century, when an obsidian mirror from Mexico made its way to England. It ended up in the collection of John Dee, advisor to Queen Elizabeth I – but more on him later.

Various indigenous cultures around the world also found meaningful visions in reflective surfaces. In parts of Africa and the African diaspora, one finds practices like scrying in bowls of water or using mirrors in folk magic (for example, some Hoodoo traditions incorporate mirrors to communicate with spirits or reflect negative spells). In Madagascar and Siberia, shamans historically wore polished pieces of metal or obsidian as pendants not just for ornamentation but as spiritual tools. These shamanic mirrors could serve as a means to see into the spirit world or as a shield to ward off malevolent entities. A Siberian shaman’s bronze mirror might be held up in ritual, allowing him to “catch” glimpses of spirits behind him or to navigate the realms he visits in trance.

Even in ancient China, mirrors were thought to have supernatural properties. Feng shui practice treats mirrors as conduits of energy, capable of either inviting or repelling spirits. One old Chinese belief is that mirrors can trap souls – it was said that if you place a mirror in front of a dying person, their soul might get confused or captured by the reflection. While not a practice of communication, this highlights the mirror’s perceived power over the boundary between life and death.

What’s remarkable is the through-line connecting all these cultures: a mirror (or mirror-like surface) provides a threshold, a meeting point between the material world and something beyond. Whether the user sought a conversation with an ancestor, a vision of a god, or an answer to a burning question, the method was similar – gaze, wait, and let the mind move beyond the ordinary.

By setting the stage – a quiet spot, a shiny surface, perhaps some ritual drama – our ancestors were, knowingly or not, leveraging psychology and belief to open themselves to extraordinary experiences. In doing so, they created early versions of the psychomanteum, long before the term existed. These practices were treated with reverence and caution. After all, gazing too long into the uncanny can be a double-edged sword: you might find enlightenment, or you might scare yourself half to death.

Forbidden Reflections: Mirrors in Medieval and Folk Lore

As we move into the early medieval era, the official stance on such practices turned dark. In much of Europe, the rise of Christianity meant that contacting spirits outside of sanctioned prayer was viewed with deep suspicion. The reflective arts – mirror gazing, crystal scrying, and anything that smelled of “pagan” divination – were often branded as sorcery or consorting with demons.

Church authorities issued warnings and even decrees against the use of mirrors for summoning spirits. An old church legend claims that St. Patrick himself declared that if any Christian claimed to see spirits (or heaven forbid, demons) in a mirror, they would be barred from communion until they repented. This stern approach filtered down through the centuries. By medieval times, an honest peasant wouldn’t dare admit to mirror scrying; to do so could earn you accusations of witchcraft.

Yet, human curiosity isn’t so easily extinguished. The practice of catoptromancy (mirror divination) went underground, surviving in the shadows of folklore and secret grimoires. Medieval grimoires (basically handbooks of magic) sometimes included instructions for conjuring spirits to appear in mirrors. One had to prepare sigils, burn incense, say Latin incantations and then peer into a consecrated mirror at the witching hour – and hope something appeared. It’s easy to imagine such a scene: an anxious sorcerer in a drafty castle tower, tracing protective circles in chalk, daring to look into the dark mirror by the light of a single tallow candle, hoping to see an angel or demon materialize to answer his questions.

Witches, in the popular imagination, also used mirrors for their craft. In ancient Thessaly (a region in Greece notorious in classical literature for witches), it was said witches could even write their oracles in blood on mirrors. This likely meant they inscribed messages from spirits or the future onto a mirror using blood, to reveal prophecies. The image is gruesome but powerful – a blood-smeared looking glass reflecting both the question and some cryptic answer from beyond.

Mirrors also became entwined with fearful folklore. Many cultures evolved the superstition that mirrors could steal or trap souls. In parts of Europe and America, a widespread custom is to cover all mirrors in a house when someone dies. The reasoning? If the ghost of the newly deceased sees itself in a mirror, it might realize it’s dead and get trapped, or worse, refuse to leave the house at all. There’s also a creepy corollary: if you see your own reflection in a room where someone has recently died, it could be an omen that you’re next. To this day, in some Southern communities (including here in Savannah’s historic quarters), families drape mirrors with black cloth during mourning, just to be safe. It’s a gesture of respect and of caution, born from a time when people truly believed the boundary between this life and the next was thinnest around death – and that mirrors, as supernatural doorways, had to be shut.

Another medieval mirror belief involved demons. It was whispered that if a devil were present in a room, you might catch a glimpse of its true form in a mirror – even if it remained invisible to the naked eye. This gave mirrors a protective role: they could expose an evil spirit hiding under a fair guise. Some even say this is the origin of vampire tales about not having a reflection; a being with no soul (like a vampire or demon) would not appear in the mirror. We can imagine villagers in a candlelit tavern, casting nervous glances at the polished metal mirror on the wall, wondering if a strange traveler’s face might fail to show up in it.

By the late Middle Ages, superstitions had multiplied. Breaking a mirror was terrible luck (seven years of misfortune, as we still say), perhaps because it “broke” a part of your soul or invited in malign forces. In Russia, mirrors are linked to the devil in folklore because of their power to draw souls out of bodies. It was also said that if you dared to look at yourself in a mirror by candlelight on a dark night, you might see the Devil himself over your shoulder. The prudent lesson: don’t indulge vanity or curiosity in reflective surfaces when the veil of night is drawn.

Amid these fears, however, people still yearned for what mirrors could do. The forbidden fruit of mirror-gazing remained attractive. Itinerant wise-women or cunning-men (practitioners of folk magic) in rural areas might quietly offer mirror divinations – perhaps a grieving parent desperate to see a lost child’s spirit one more time, or a lovelorn youth wanting a glimpse of their future spouse. The official church line would condemn it, but behind closed doors, the mirror-in-the-dark continued to captivate. In many ways, the psychomanteum went incognito during this era, disguising itself in superstition and whispered ritual, waiting for a renaissance (literally) to come.

The Renaissance Occult Revival: Dr. Dee and the Queen’s Mirror

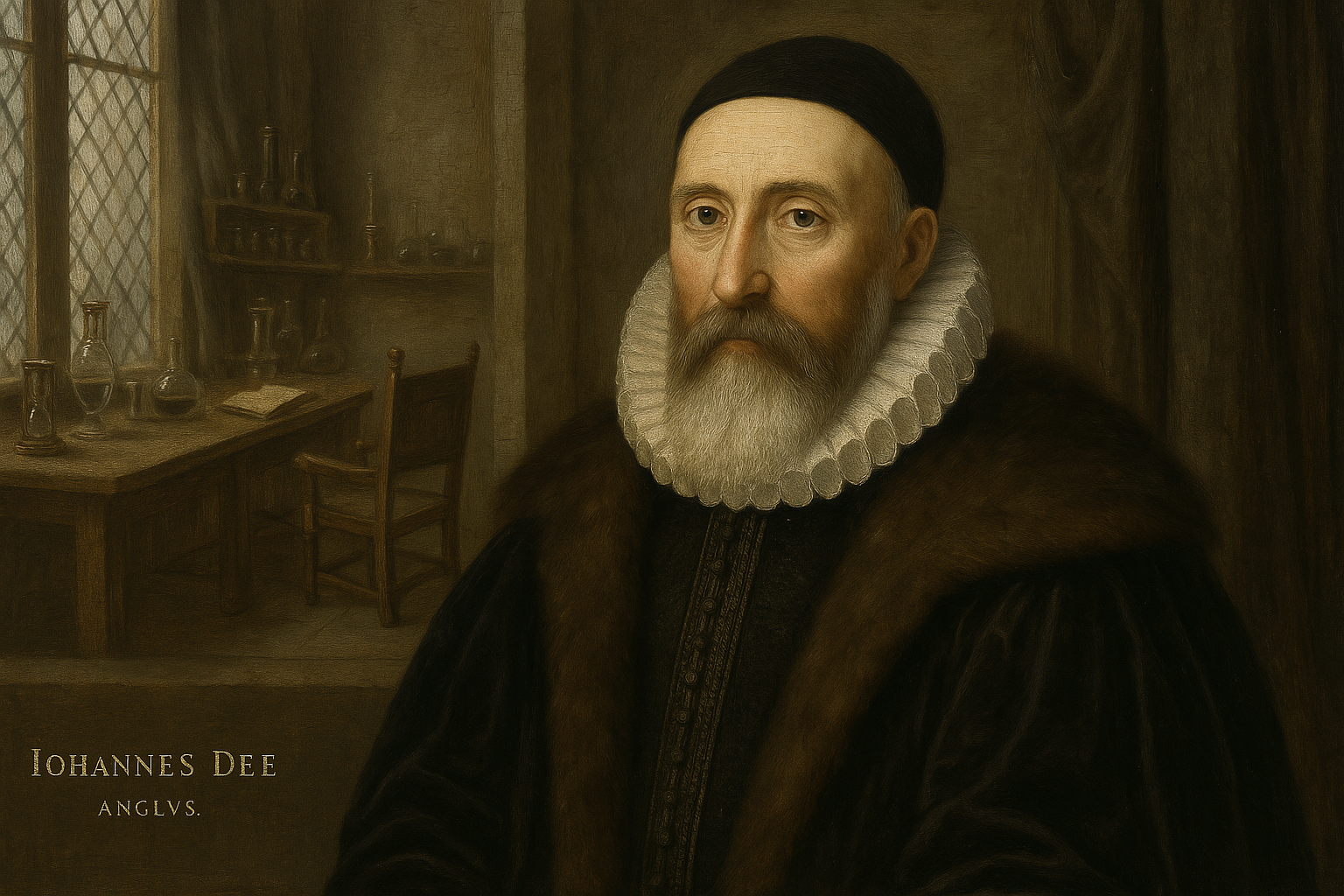

The Renaissance (15th–17th centuries) brought a new wave of interest in all things mystical, mirrors included. This era was a peculiar mix of scientific awakening and occult exploration. Scholars and nobles often dabbled in magic, seeing no contradiction in studying mathematics one day and trying to summon angels the next. It’s here we meet John Dee, one of the period’s most famous magus figures, and a great lover of scrying mirrors.

Dr. John Dee was a true Renaissance man – mathematician, astronomer, navigator, and also the personal astrologer (and advisor) to Queen Elizabeth I of England. But behind closed doors, Dee spent many years attempting to communicate with otherworldly intelligences. He believed, as did some learned contemporaries, that with the right tools and rituals, one could converse with angels or spirits who would impart divine knowledge.

One of Dee’s prized possessions was an obsidian mirror – a perfectly round, polished black disk about the size of a hand mirror. This exotic artifact had arrived from Mexico, likely taken from the Aztecs, and eventually found its way to Dee’s study. In his diaries, Dee called such items “shewstones” (show-stones), whether they were crystal balls or mirrors, because they “showed” visions. Dee worked with several scryers (people supposedly gifted with second sight), such as the notorious Edward Kelley. Kelley would gaze into the mirror and describe aloud what he saw, while Dee sat nearby, diligently recording every detail. Through this method, they claimed to receive messages from angelic beings, written in a strange script (what we now call Enochian, an angelic language that Dee transcribed from these sessions). The goal wasn’t exactly to chat with Grandma’s ghost – it was loftier, to learn secrets of the universe – but the mechanism was essentially a psychomanteum session: two men and a mirror bridging worlds.

Picture Dr. Dee in his dim study at Mortlake, London. Evening has fallen. Beeswax candles flicker on the table, illuminating shelves of leather-bound books and strange instruments. A curl of incense smoke hangs in the air, sweet and heavy. On the table lies the obsidian mirror, its surface like a circle of pure midnight. Dee murmurs Latin prayers and invocations from his grimoires, hoping to attract benevolent angelic forces. Opposite him, Edward Kelley peers intently into the black glass, eyes wide but relaxed, almost in a trance. Suddenly Kelley stiffens slightly: “I see a figure…” he begins. Dee’s quill scratches on paper, recording every word. Kelley describes a tall being in flowing robes appearing in the mirror’s depth, delivering a message of mystical import. Dee interjects gentle questions, seeking clarity, all the while chronicling this ethereal conversation.

For Dee and those like him, the mirror was not superstition but a scientific instrument – a “device” to extend human perception into invisible realms. We might smile at that notion now, but consider that Dee was also a forward-thinking mathematician; he saw no conflict between arithmetic and angelic prophecy. In his quest, the mirror provided evidence (to him) that consciousness could reach beyond itself and contact other intelligences. Was Kelley truly seeing angels or merely spinning tales? History leaves that debate open. But the fact remains: the highest echelons of Elizabethan society did not dismiss the possibility that a mirror could serve as a hotline to heaven (or hell).

Dee wasn’t alone in his fascination. Nostradamus, the famed French seer of the 1500s, is believed to have practiced mirror or water scrying. Accounts say he would sit at night, a brass bowl filled with water (sometimes with a drop of ink to darken it), placed on a tripod. Staring into the shimmering dark liquid, Nostradamus would enter a meditative state in which vivid images of the future swam up before him – visions he later penned as his famous quatrains of prophecy. It’s essentially the same method: a reflective surface, deep focus, and an intention to see beyond ordinary sight.

Even royals dabbled. Catherine de’ Medici, the powerful queen mother of France, was rumored to own an enchanted mirror. She purportedly consulted it to glimpse coming events and guide the fate of her kingdom. While the details are murky, the very existence of such rumors in the historical record shows how commonplace the notion of magical mirrors was at the time. Far from being mere superstition of peasants, mirror divination was an art courted by the educated and powerful when it suited their needs.

By the 17th century, the Enlightenment’s rational winds began to blow, and overt occult practices at court fell out of fashion. John Dee’s mirror ended up as a curiosity piece (today it sits in the British Museum). Science advanced, and technology for observing the natural world (microscopes, telescopes) took center stage over methods for observing the spirit world. Still, behind closed doors, the lineage of the psychomanteum quietly persisted, handed down in secret societies, occult orders, and folk practices. The mirror remained – waiting for its resurgence in a more modern time, under more experimental eyes.

Scrying in the Age of Spiritualism: Victorian Mirror Visions and Ghost Stories

As the 19th century rolled in, interest in contacting the dead experienced a massive resurgence, culminating in the Spiritualist movement. People gathered in parlors to hold séances, table-turning parties, and automatic writing sessions – all attempts to commune with spirits. Oddly, mirror-gazing was not the central tool of Victorian Spiritualism (mediums, spirit trumpets, and Ouija boards were more common), but it still had a presence in the era’s supernatural landscape.

Victorians adored ghost stories, and mirrors often featured in these tales as haunted objects or eerie portals. Consider the enduring legend of “Bloody Mary.” The classic dare goes like this: in a dark room, with only a candle or two, one gazes into a mirror and chants “Bloody Mary” (or a similar incantation) a certain number of times. According to fearsome folklore, the bloody-faced specter of a woman – Mary – will appear in the mirror, sometimes as a corpse, sometimes raging, perhaps even emerging to scratch the summoner. Many a teenage girl in Victorian times (and to this day) scared herself silly with this game during sleepovers. Some trace the legend’s origin to Queen Mary I (“Bloody Mary” for her violent reign), others to a witch named Mary Worth. Either way, the concept is pure psychomanteum: perform a ritual, gaze into a mirror, and call forth a spirit. Only here, the goal is fright rather than comfort, a reflection of the mirror’s spooky reputation.

Beyond party games, there were serious reports collected of mirror apparitions. In 1882, the newly founded Society for Psychical Research (SPR) conducted a “Census of Hallucinations,” surveying thousands on whether they’d ever seen an apparition. Many respondents described looking in a mirror and seeing a deceased relative standing behind them, or glimpsing a unknown face that vanished. One famous case: a man staying at an inn saw in the mirror of his room the distinct image of a bedraggled old woman peering over his shoulder. When he spun around, no one was there. Later he discovered the room had a history – a previous occupant, an old woman, had died there. Such accounts, while anecdotal, reinforced the public’s sense that mirrors could invite ghosts unbidden. Perhaps the mirror was simply a trigger for the mind to produce what it feared or expected – or perhaps, as Spiritualists believed, a mirror was genuinely a window through which spirits could look back.

Interestingly, some Victorian experimenters intentionally tried mirror-gazing as part of spiritualistic investigations. Members of esoteric groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn used black mirrors (often a piece of dark glass or polished obsidian) for scrying. Florence Farr, a notable Golden Dawn adept, was said to enter trance states while gazing into such a mirror, reporting travels on the astral plane. In the U.S., the “Witch of Lime Street” Mina Crandon, a famous medium of the 1920s, occasionally incorporated a mirror in her séances to see spirit guides. It wasn’t mainstream within Spiritualism, but it was around, especially for those inclined to more ancient-style practices.

Meanwhile, the public devoured ghostly fiction. Haunted mirror stories became a trope. For instance, an 1850s tale might recount a newlywed couple moving into a manor and discovering an old mirror covered in a corner; polish it up, and they start seeing the tragic ghost of a previous occupant reliving her sorrow. Such motifs cemented the mirror as a symbol of the past’s hold on the present. Even in high literature, we find mirror magic – Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871) spun a whimsical take on the idea of entering a mirror-world. Oscar Wilde, in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), turned the concept inward: a portrait (akin to a mirror) secretly recorded all of a man’s sins and aging, reflecting his soul while his face remained innocent. That’s not a ghost story per se, but it uses the mirror idea of hidden truth and supernatural reflection.

On the home front, folk practices persisted. One charming (if creepy) Victorian divination game instructed unmarried young women to eat a salted herring at midnight before bed, then stand in front of a mirror. Legend said they would see the face of their future husband appearing over their shoulder (supposedly to offer water because they’d be thirsty from the salt!). If instead they saw a skull, it meant they’d die before marrying. Such parlour diversions were half in jest, half taken to heart – again demonstrating how ingrained the mirror’s mystical role was, from serious mourning rituals to lighthearted fortune-telling.

By the turn of the 20th century, the explicit use of psychomanteums as the ancients did was not widely practiced or studied. It would take another man of science – Dr. Moody – nearly a hundred years later to revisit the mirror method with a clinical eye. But the Victorian era kept the flame alive through its stories and occasional experiments, ensuring that the concept of the mirror as a portal never really faded from cultural consciousness.

The Modern Psychomanteum Revival: Dr. Raymond Moody’s “Theater of the Mind”

Fast forward to the late 20th century: in a quiet, dim room stands a large mirror, and before it sits a curious researcher. Dr. Raymond Moody, the man who coined the term “near-death experience” (NDE) in 1975, turned his attention to psychomanteums in the 1990s. Through studying NDEs, Moody noticed a common thread: people often encountered deceased loved ones during these episodes, which brought immense comfort and altered their views on death. Separately, he noted how often the bereaved reported seeing or sensing their lost loved one in the days or weeks after the death – spontaneous “after-death contacts.” These observations led to an intriguing question: Could we create conditions to facilitate these comforting encounters on purpose, in a controlled, safe way?

Moody dug back into history and was struck by the accounts of ancient Greek oracles of the dead and the practice of mirror-gazing through the ages. In 1992, he constructed a modern psychomanteum in a rural Alabama farmhouse – a place he playfully dubbed his “Theater of the Mind.” It was essentially a small room devoted entirely to inducing visions. The setup followed what we’ve discussed: one wall hung with a tall mirror, a comfortable armchair set about three feet in front of it, and black velvet curtains draped around to eliminate any stray reflections. A single lamp with a low-watt bulb (or a candle) was positioned behind the chair as the only light source. The person sitting would see only darkness in the mirror. This was Moody’s laboratory for afterlife encounters.

But Moody didn’t simply plop people down and say “see a ghost!” He developed a thorough preparation process. Participants (often those grieving a specific loss) were instructed to spend about an hour beforehand in a relaxed state, looking at photographs or personal items of the loved one they hoped to contact, and reminiscing about positive memories. This focused their intention and brought the person vividly to mind. Moody likened it to priming a pump – filling the mind and heart with the desired connection. Only after this would the participant enter the mirror room. They were encouraged to sit calmly and gaze into the darkness of the mirror for an extended period (usually up to 45 minutes or an hour), without forcing anything, just keeping an open, passive mind.

The results were astonishing and surprisingly consistent. Dr. Moody reported that in his first structured study of 50 individuals, about half experienced what they perceived as a successful contact. Some saw an image in the mirror – often dim at first, then coalescing into the clear form of the departed. Others actually felt the person “step out” of the mirror and appear in the room to embrace or converse with them. A few only heard a voice, or simply felt a presence strongly without visual confirmation. The encounters were almost uniformly emotional and impactful. Many participants burst into tears – not of fear or sadness, but of overwhelming joy or relief. It was common for them to describe the apparitions as looking younger, healthier, or “glowing.”

Crucially, participants often reported that the interactions felt entirely real – like actual visits, not daydreams. They spoke of hugging their lost spouse and feeling a solid form, hearing their father’s familiar timbre of voice telling them he was okay, or smelling their mother’s favorite perfume in the air as she appeared. And the effects were long-lasting: people emerged with a sense of peace, comfort, and a drastically reduced fear of death. In follow-ups, Moody found that these individuals felt their grief had transformed – the mirror encounter served as a form of closure or reassurance that life continues in some form.

To illustrate one of Moody’s case studies: A middle-aged man named John (pseudonym) lost his teenage daughter in a car accident, leaving him in profound despair. In the psychomanteum session, John gazed into the darkness and eventually saw a bright mist forming. The mist cleared into an image of a beautiful young woman – it was his daughter, smiling radiantly. She conveyed to him (without speaking aloud) that she was happy and surrounded by love. John even saw fleeting images of other deceased relatives with her, as if to say “we’re together.” The vision lasted only perhaps 30 seconds, but afterward, John reported an enormous weight lifted from his heart. He was convinced he truly saw her spirit and that she was at peace, which allowed him to begin healing.

Not everyone had such a vivid experience. Some only saw swirls of light or a partial face that faded away, leaving them unsure. Others saw nothing during the mirror session, but interestingly, later that night they might dream of the person or have a sudden “visitation” experience at home. Moody called these delayed effects “take-out visions,” likening it to taking the experience home like leftovers. In one case, a woman who desperately wanted to see her deceased husband had no luck in the chamber beyond some foggy shapes. Disappointed, she left – but that night, she awoke to find an apparition of her husband standing at the foot of her bed, comforting her. This happened within 24 hours of the mirror attempt, and she felt it was directly connected.

Over the years, Moody worked with hundreds of individuals and became convinced that the psychomanteum was not only a valid method for inducing after-death contacts, but also that it had tremendous therapeutic potential. In his 1993 book Reunions, he detailed these findings and reflections. He noted patterns like:

- People often encountered someone other than the person they intended – as if the experience had its own wisdom (e.g., trying to contact Mom but instead Uncle Joe’s spirit comes because maybe there’s unresolved business there).

- Roughly 25% reported some physical sensation of contact (like being touched or hugged by the apparition).

- A small fraction felt a sense of entering the mirror themselves, glimpsing a world or landscape “beyond” (comparable perhaps to near-death experiencers who describe entering another realm).

- A significant number had that delayed experience later, rather than in-mirror.

- Virtually all who “made contact” asserted it was no hallucination or dream – in their gut they felt it was real.

Given Moody’s credibility from his NDE research, the mainstream took some interest, though with skepticism. Psychologists pointed out that these were prime conditions for the brain to generate comforting illusions – essentially a guided self-hypnosis tapping into memory. Moody didn’t entirely disagree that psychological mechanisms were at play, but he also didn’t rule out a genuine paranormal aspect. He remained scientifically agnostic yet personally moved by what he witnessed.

The important takeaway is that the modern psychomanteum was born. Moody’s work reignited curiosity in mirror-gazing beyond the fringe. Other researchers attempted to replicate or modify his methods. For example, in the 2000s, psychiatrist Dr. Raymond Moody (collaborating with others like Dr. Charles Tart) and even some grief counselors quietly integrated mirror-gazing for patients who seemed likely to benefit. The results tended to echo Moody’s: not everyone sees a ghost, but those who do often find it life-changing in a positive way.

Moody himself emphasized that the experience, even if “just” a product of one’s mind, carried profound psychological healing. And if it was something more – well, that was a revelation for the ages. Either way, he advocated that psychomanteums be used responsibly, guided by someone knowledgeable, especially for grief therapy. He cautioned that it’s not a carnival trick or something to do out of mere curiosity about ghosts; it works best when the need is genuine and the intent pure.

By the 21st century, the psychomanteum thus stood at an intriguing crossroads: a millennia-old practice now being studied with modern eyes, yielding results that challenge our understanding of perception, grief, and perhaps the permeability of the boundary between life and death.

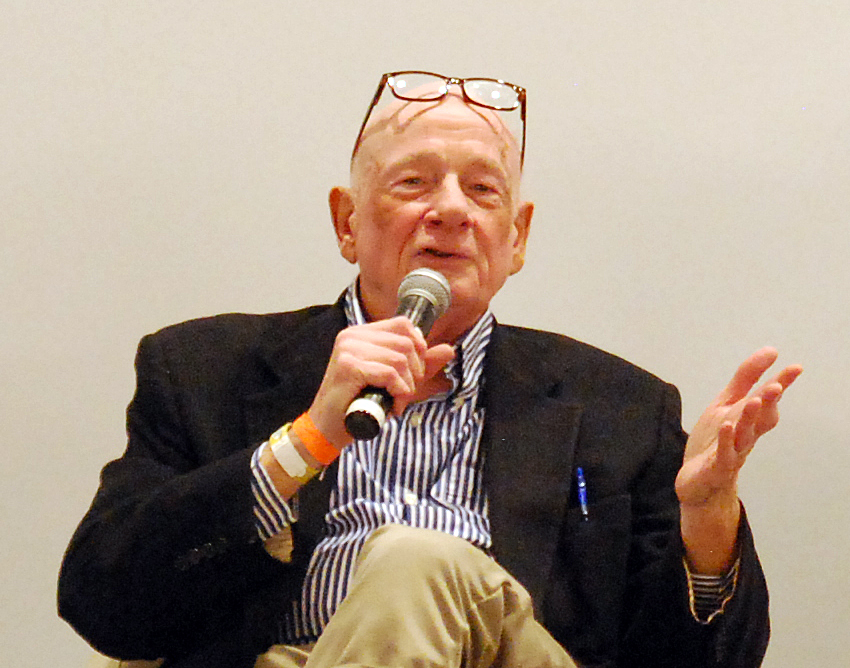

Dr. Raymond Moody

Inside a Psychomanteum Session: What It’s Like

It’s one thing to discuss history and results, but to truly appreciate psychomanteums, we should try to feel the experience. Of course, reading about it is not living it – but let’s construct a vivid scenario based on many first-hand accounts, to get a sense of the atmosphere and emotions involved.

Imagine you are the participant. You’ve come to a psychomanteum seeking a reunion with someone dear – say, your grandmother who passed a few years ago. She practically raised you, and you miss her terribly. The facilitator has gently guided you through the preparatory steps throughout the afternoon. You sat quietly flipping through an old album of photos: grandma baking pies in her sunny kitchen, grandma laughing in the garden, the two of you dancing at a wedding. You’ve brought her favorite brooch with you – a small rose carved in ivory – and you hold it, warm in your palm, thinking of her voice, her scent, her unconditional love. By twilight, you feel emotionally tuned to her, a mix of longing and calm readiness.

Now, as dusk deepens, you enter the psychomanteum chamber. It’s a small room; the walls and even the ceiling are draped in black velvet curtains that swallow the light. The air is still, almost thick in its silence. You notice a comfortable high-backed armchair facing one wall. There hangs a mirror – large, rectangular, its frame lost in shadow so that it appears like a doorway of pure darkness. A single floor lamp stands behind the chair, its bulb casting a low amber glow upward.

You settle into the armchair. It’s plush and enveloping, allowing you to completely relax your body. The facilitator’s whisper: “Take your time. Simply gaze softly into the mirror. Don’t try to force anything. We’ll be right outside if you need us.” The door clicks shut, leaving you alone.

At first, your posture is a bit stiff with anticipation. You consciously unclench your jaw, let your shoulders drop. The silence is profound – you can hear your own heartbeat in your ears for a moment, but it slows as you breathe in a measured, meditative way. In your hand, you still clutch grandma’s brooch, feeling the etched petals under your thumb. That tactile link to her gives you comfort.

You direct your gaze at the mirror. Or rather, into the mirror – since it reflects only darkness, it’s like looking into a deep well at midnight. You see nothing, save maybe the faintest hint of the lamp’s glimmer far behind you. If you focus, you can make out where the mirror’s edges are by tiny differences in the blackness. But after a while, you stop trying to focus. You let your eyes relax, almost as if staring “through” the mirror, not at its surface.

Time loses meaning. It could be ten minutes or thirty. You’ve drifted into a state where your breathing is slow and your thoughts subtle. Memories of grandma float up naturally: her humming a tune, the feel of her cool hands when she’d fix your collar, the way she called you by a pet nickname. You might whisper, “Grandma…” once, your voice tiny in the room, just to reinforce your invitation.

Then, something begins to change in the mirror. You’re not sure at first if it’s real or imagined, but the darkness is not uniform anymore. There is a patch – toward the center – that seems darker than the surrounding dark, if that makes sense. A velvety black within black, which gradually becomes a swirling gray mist. Yes, you definitely see a foggy form collecting in the mirror, like a cloud manifesting behind glass. Your heart gives a slight jolt; you inhale sharply but keep your eyes glued to that spot, afraid to blink too much.

The mist thickens and starts to take shape. It’s almost like watching an artist sketch with smoke – you perceive outlines emerging. Shoulders, a head. Two glowing areas that might be eyes. It’s faint, but growing clearer by the second. The figure is seated, then perhaps standing… no, walking forward. Details fill in: a familiar floral-patterned dress, soft white hair styled in a bun, a tiny woman with a kind, wrinkled face. A hand clutches a small object at her chest – is that the locket you made for her in 10th grade? Tears prick your eyes as recognition dawns.

It’s her. Grandma is there, in the mirror, as though standing in a dimly lit space that isn’t your room. She looks vibrant, at peace, even smiling gently as her eyes meet yours. You instinctively murmur, “Grandma?” Your voice cracks. She nods, still smiling. You can barely breathe from the emotion welling up.

Now she steps forward – and unbelievably, it appears she is stepping out of the mirror. One moment she was an image on the other side of the glass; the next, it’s as if she crosses some threshold. You don’t dare turn around to see if she’s “actually” behind you in the room – you keep watching the mirror, and in it you see her form approaching your chair, within your space. The boundary between mirror-world and this world dissolves.

Suddenly, you feel a hand on your shoulder – that gentle, warm squeeze you remember so well. It is simultaneously shocking and utterly natural. A sob escapes your throat, but it’s a sob of joy. You look up (in the mirror it shows you tilting your head) and see her face nearer to yours. Though you see her lips move, you hear her words not with your ears but inside: “I’m here, sweetheart. I love you.” It’s exactly her voice, tender and playful. You nod rapidly, tears streaming now. “I love you too… I miss you,” you manage to whisper aloud.

For what feels like an eternity (but is likely less than a minute), you have a wordless communion. Thoughts and feelings flow – you convey your gratitude, your life updates, even your guilt over not visiting the week before she died. She communicates reassurance, pride in you, and importantly that she is fine, more than fine, where she is. You feel forgiveness, acceptance, overwhelming love.

At one point you reflexively reach up to touch the hand on your shoulder – your fingers brush something, but it’s more like a tingle than a solid hand. In the mirror you see her form flicker slightly as you do that, so you stop, not wanting to disrupt this fragile miracle.

Eventually, she steps back, slowly. Perhaps you hear in your mind her familiar parting phrase, “Don’t you worry about me, I’ll be seeing you again.” You choke out, “Thank you… I’ll try not to worry.” She winks – actually winks – just as she used to when imparting a bit of playful secret. Then, like mist, her form recedes. She is backing away, and the gray fog folds around her. For a moment her face is visible in the mirror’s depth, and you try to imprint it on your mind – she looks younger than when she passed, happy and whole. Then the darkness reclaims the mirror. She’s gone.

You exhale a huge breath you didn’t realize you were holding. You feel simultaneously stunned and comforted. The room is just a room again, the mirror just a mirror. The only evidence of anything out of the ordinary is your emotional state and the dampness on your cheeks. You sit for a moment, whispering “Thank you” under your breath to the universe, to the mirror, to whatever allowed that to happen.

When you finally stand and leave the room, the facilitator sees your face and knows – you saw something. They speak with you gently as you excitedly and tearfully recount how real it felt. You even still smell a hint of your grandma’s vanilla perfume on your sleeve. You feel not a shred of fear. Instead, a profound peace and a kind of awe: death is not the end, and love truly seems to transcend physical boundaries. It’s a gift you’ve been given, and you know it.

This scenario, minus personal specifics, echoes dozens upon dozens of reports. People consistently describe that initial mist, the eventual clarity of the apparition, often an attempt at communication (sometimes spoken aloud, sometimes telepathic or emotional), and then a fading away. They describe sensations of presence, occasionally physical touch or temperature changes. Many, like in our imagined account, cry not out of sadness but from the overwhelming sense of reunion. The atmosphere is typically described as reverent, calm, and deeply moving – not like a horror movie jump-scare or a spooky haunting.

Of course, not every experience goes so perfectly. Sometimes the person only sees a face that smiles and vanishes without “interaction,” which can be frustrating or leaves them wondering what it meant. Sometimes, though rarely, someone might see something unsettling, usually tied to their own fears (hence the guidance that you should attempt this only when emotionally stable and with positive intent). But overwhelmingly, the experiences in Moody’s research were positive and often life-altering in a healing way.

Reading this, one may feel skeptical – it does sound almost too good to be true, like wish fulfillment. And indeed, that’s one strong interpretation: the brain might be generating a vivid lucid-dream-like sequence in a suggestible state. But to those who go through it, the subjective reality is powerful. It can turn a staunch skeptic into someone who at least entertains that consciousness might extend beyond death, or at minimum, that the mind has depths we scarcely fathom.

Skepticism and Science: Between Psychology and the Paranormal

Given the remarkable nature of psychomanteum experiences, it’s essential to approach them with a balanced, critical eye. Are people truly meeting spirits, or are they effectively meeting their own subconscious under the theater of a ghostly encounter? As with many things paranormal, the answer might not be clear-cut.

Let’s consider the psychological perspective first:

Modern psychology has long known that the brain can create incredibly realistic hallucinations under certain conditions. Sensory deprivation (like staring into a uniform dark surface in silence) is one such condition that can produce visual and auditory phenomena. The mind, starved of input, begins to fill in the blanks. The mirror provides a focal point and also a bit of feedback (the faint reflection of that lamp/candle can, as your eyes relax, morph into shapes and movement courtesy of an effect called the Troxler effect – where unchanging stimulus in peripheral vision fades or alters). Many experimenters note that after staring a while, they see the mirror cloud or their own face distort (if it’s visible). That’s not supernatural; that’s a known optical brain trick.

Now add expectation and desire. A grieving person desperately wants to see their loved one. In a dim, hypnotic environment, the brain may oblige by essentially dreaming while awake. The fancy term is hypnagogic hallucination, akin to what sometimes happens as you fall asleep – vivid images or sounds that feel real in the moment. The psychomanteum procedure (quiet, focus on a mental image, then stare blankly) is somewhat like a self-hypnosis or induced daydream.

It’s also worth noting that Moody carefully chose participants who were emotionally stable and had an open mind about such possibilities but were not hardcore spiritualists. He didn’t want highly imaginative occult zealots (who might be too eager to conjure something, even unconsciously), nor did he want people in extreme grief or unstable (for fear a negative hallucination could upset them more). So his participants were often people receptive yet measured. One could say these were ideal conditions to produce controlled hallucinations that align with what the person hopes to see.

Critics also point out the therapeutic bias: people who undergo this want to find meaning and comfort. Thus, afterward they might interpret any ambiguous flicker as “I definitely saw Mom, it was real!” Our memories are malleable; we might embellish the experience unintentionally when retelling it, making it sound clearer and more interactive than it was. Think of dream recall – how we sometimes add coherence to a jumbled dream when describing it. Perhaps some of these accounts gain vividness in retrospect due to the emotional need for them to be real.

Furthermore, consider cold reading or self-suggestion: in medium séances, sitters often take generic statements and fit them to their loved ones. In a mirror session, a participant might similarly project specifics onto a vague apparition. For example, see a generic female shape and decide it’s Grandma because that’s who you want; then every subtle impression is interpreted in that light (“Oh she’s holding something – yes, Grandma always held her rosary, that must be it,” whereas another person might think it’s a necklace or nothing at all). The mind can shape a neutral stimulus to match our hopes.

Neurologically, there’s also the possibility of micro-epileptic events or peculiar brain states in the temporal lobe that can cause feelings of presence or vision of people. Some researchers have speculated that intense concentration and sensory monotony could trigger a mild trance akin to certain epilepsy aura states (without the seizure) – during which people sometimes report spiritual visions.

Alright, now to the paranormal perspective:

Those in favor of the paranormal reality of psychomanteums argue that the consistency of experiences and the profound changes in people point to more than self-delusion. They note that many participants were initially skeptical or uncertain anything would happen, yet they had striking encounters. If it was purely driven by belief and imagination, one might expect more obviously fanciful or varied “visions.” Instead, the apparitions generally behaved and appeared in line with how one might expect an actual spirit to: conveying sensible messages, appearing healthy and peaceful, sometimes even imparting information the person didn’t know. There are anecdotes (though rarer) of someone seeing a relative in the mirror who delivers a piece of verifiable information (e.g., “I hid the will in the blue chest”) which later checks out. Those cases are gold for those who argue for an external reality.

From a spiritual view, the mirror isn’t causing hallucinations; it’s facilitating a shift in consciousness. It helps the participant reach a receptive, liminal mental state where the veil between worlds thins. Just as a radio tuned to the right frequency picks up a broadcast, the person tuned by the psychomanteum might genuinely pick up the presence of a spirit. The mirror, being a symbolically powerful object long associated with reflection and alternate views, could serve as a focal point for spiritual energy – a notion mirrored (there’s that pun again) in countless traditions. Perhaps spirits find it easier to manifest via reflective surfaces (hence so many ghost stories involving mirrors or water). Some paranormal theorists suggest that spirits are composed of or manipulate energy, and mirrors can concentrate ambient energies – making it a stage on which they can project an image or interact.

There’s also the instrumental transcommunication angle: if we set aside human perception and use devices, can we detect anything unusual during mirror sessions? Moody himself didn’t do much of this, but others have. A few attempt to measure room temperature drops, EMF fluctuations, or capture EVPs (ghost voices) during sessions. The data is far from systematic, but there are intriguing blips – like a distinct voice on tape responding to a participant’s spoken question, or a video recording capturing a light anomaly exactly when the person saw the apparition step into the mirror. While none of this is conclusive evidence, it hints that sometimes something “independent” of the person might be at play.

And of course, the subjective impact on individuals cannot be dismissed casually. Hallucinations usually don’t lead to sustained personal transformation for the better; once you realize it was your mind, the effect might diminish. But many psychomanteum experiencers hold on to the reality of what happened with conviction comparable to those who have had near-death experiences or witnessed outright apparitions in haunted locations. They will say, “I know what I felt and saw. It was real.” They’ll change life decisions, lose their fear of death, or feel ongoing communication (like sensing the loved one around in daily life more). One might argue even if it was “just in their head,” it acted as a powerful placebo or psychological catalyst for healing. But at a certain point, if the outcomes mirror (that word again) those as if it were real, some will ask: what’s the functional difference? Maybe it is real in a way we don’t yet understand scientifically.

In trying to understand such phenomena, some researchers propose a middle-ground concept of “exceptional mental states.” In these states, the mind might access information or create experiences that aren’t normally available. This could include telepathy, clairvoyance, or contact with discarnate consciousness – all taboo in mainstream science, but actively researched in parapsychology. The psychomanteum could be a tool that reliably induces an exceptional state where, for example, a part of your consciousness reaches out across time/space (or to “the other side”) and genuinely connects with the deceased – but our brain renders that exchange in the dramatic form of a vision so our waking self can comprehend it.

Even some skeptically-minded folks have softened after trying mirror-gazing themselves. Psychologist Dr. Raymond Moody (being both researcher and somewhat of a participant in his own experiments) wrote that his own encounter in the mirror with a deceased relative left him personally convinced that something beyond a self-generated hallucination occurred. He felt things during that encounter (like a telepathic communication and emotional resolution) that went beyond what he anticipated even knowing the mechanisms. Of course, a skeptic would counter he’s primed to believe and likely to attribute meaning. And around it goes.

From a strictly scientific standpoint, to “prove” something paranormal, one would need objective evidence – like a reading on a device that correlates strongly with the reported apparition, or the person obtaining verifiable info they couldn’t have known. Few controlled studies have been done with those metrics, and those that have yielded small hints but nothing earth-shattering. So mainstream science still files psychomanteum results under “interesting psychological phenomena.” Yet, the door remains open a crack. The experiences, at the very least, remind us that human perception is not fully charted territory. Even if entirely brain-born, how fascinating and poignant that our minds can craft such encounters that mend our hearts!

In the end, many who delve into this subject take an agnostic but appreciative stance: they acknowledge the psychological explanations but don’t discount the possibility that some experiences are genuinely transcendent. After all, for the experiencer, the value is real either way. Grief was alleviated. Personal meaning was gained. If it was a gift from the unconscious, it’s no less a gift. And if it truly was grandma’s spirit paying a visit, then perhaps science will catch up with that truth someday.

Psychomanteums Today: Ghost Hunting and Personal Journeys

Since the 1990s revival by Dr. Moody, psychomanteums have slowly entered the lexicon of paranormal investigation and even popular culture. They’re not as commonly referenced as Ouija boards or EMF meters, but among dedicated ghost hunters and spiritual explorers, the idea of a “mirror portal” is well-known.

In ghost hunting circles, some teams incorporate mirror gazing into their investigations of haunted locations. For instance, a paranormal TV show might feature investigators setting up a makeshift psychomanteum in a notoriously haunted house. Picture two mirrors propped to face each other in a dark attic (creating that infinite reflection tunnel said by lore to open portals), with an intrepid investigator sitting between them calling out to spirits. This exact scenario played out on an episode of a Travel Channel series, where the ghost hunters attempted to lure out a spirit by essentially giving it a mirror gateway. They reported seeing a shadow figure briefly in one of the mirrors and captured a strange light on camera – nothing conclusive, but enough to make good television and suggest that the spirit might have peeked through.

Another investigative approach is to use a single large mirror in a haunted room, turn off all lights, and have one person do the classic psychomanteum gaze while others monitor. In one case, a researcher in a reputedly haunted theater sat before an old dressing-room mirror (the kind with dim bulbs around it), hoping to see the rumored ghost of an actress. After 20 minutes, he suddenly saw a face that wasn’t his – a woman’s face with sorrowful eyes – and simultaneously the team’s audio recorder picked up a faint sobbing sound that hadn’t been audible in the room. Incidents like these, while rare, intrigue even the skeptical: if two different senses (sight via the witness and sound via the recorder) both align on an experience, it strengthens the case that something objective might have occurred.

On the DIY front, individuals sometimes create their own home psychomanteums. Perhaps they’ve read Moody’s books or a summary online and are curious to try contacting a loved one without going to a formal researcher. Online forums exist where people share tips: a quiet room, a mirror angled correctly, personal mementos, maybe a short meditation beforehand. They also share results – these range wildly. Some come back excited: “I did it! I saw my dad and it felt so real. We even ‘talked’ (in my mind). I’m blown away.” Others might say they only got spooked by their own mind (one user joked that he ended up seeing “Bloody Mary” instead because he spooked himself imagining her and aborted mission).

There’s generally a caution passed around: Approach with the right intent. If you’re just thrill-seeking or trying to summon any random ghost for fun, you might invite confusing or scary experiences (or nothing at all). But if your heart is in a place of love or genuine seeking, you’re “protected” in a sense by your own positive energy, according to psychomanteum enthusiasts. Even if one doesn’t buy the mystical side, psychologically that makes sense – your mindset will influence what you perceive.

Some mediums and spiritual practitioners have integrated mirror scrying with other techniques. For example, a medium might use a black mirror to enhance their visions during a reading, claiming it helps focus their clairvoyance. A few mediums in the UK have even offered “mirror séances” where a small group all gaze into a big mirror hoping to collectively see a spirit. Reports from such gatherings say sometimes everyone saw the same face appear – which is harder to chalk up to individual imagination. Could mass suggestion cause group hallucination? Possibly, or perhaps there really was a visible manifestation.

There’s also an overlap with ITC (Instrumental Trans-Communication) – a field where people try to use electronic devices to communicate with spirits (like recording EVP or using Spirit Boxes). Some ITC experimenters use video feedback loops (pointing a camera at a screen showing its feed, creating swirling visuals) which is like an electronic psychomanteum, yielding weird faces in the static. The mirror is just the low-tech version of that idea. And indeed, some ITC folks have aimed cameras at mirrors in the dark to see if any spooky images show up on the recording that maybe the human eye missed. Occasionally, frames of such footage circulate with what looks like a faint figure in the mirror that wasn’t seen at the time – pareidolia (seeing patterns like faces in random data) is likely at play, but who knows?

On the therapeutic front, while it’s not mainstream, a few grief counselors or therapists with an interest in the transpersonal have quietly used psychomanteum techniques. They might not call it that, perhaps dubbing it “guided reflection therapy” or something more palatable. The idea is to facilitate a controlled visualization for grief resolution. Sometimes even without a mirror, therapists will do a guided imagery: “Close your eyes and imagine your loved one coming into the room…” Essentially, the mirror just externalizes that internal process so the person can keep eyes open (which some find easier than pure imagination). One researcher, Dr. Allan Botkin, developed a therapy called Induced After-Death Communication (IADC) using EMDR (a trauma therapy) to achieve something similar – patients often report vivid, healing visions of their loved one after the procedure. This suggests there are multiple ways to evoke these experiences.

The ethical discussion also comes up: is it okay to induce such things, especially if one believes it’s imagination? If the person believes they truly spoke to their loved one, is that fostering a potentially false belief? Or is it a benign “white lie” of the psyche that helps them heal? What if someone starts obsessing over mirror gazing, trying to do it repeatedly to stay in contact – could that hinder moving on? These are valid concerns. In practice, though, most people who succeed at it don’t feel the need to do it constantly; the experience tends to give peace and reduces obsessive grief rather than increasing it. And those who don’t get results usually just shrug and move on (or seek other avenues like mediums).

In popular media, the mystique of the psychomanteum continues. A recent horror film might have a scene where a character, out of desperation, sets up a mirror ritual to contact a dead child – with cinematic results far more dramatic and usually sinister (Hollywood likes to add a demon or evil spirit creeping through instead of kindly Grandma). This unfortunately perpetuates the notion that all such practices are flirting with danger. In truth, the vast majority of historical and modern accounts have not encountered “demons” via mirror (Bloody Mary games aside). But the spooky vibe is hard to shake; many people, even rational ones, admit they feel uncomfortable around mirrors in dark rooms because of these cultural stories.

Finally, on a lighter note, haunted locations with famous mirrors have become tourist attractions. For instance, the plantation home “The Myrtles” in Louisiana has a mirror that is said to contain the spirits of a mother and children poisoned long ago – visitors frequently take photos of it hoping to capture mysterious handprints or faces (and some do capture anomalies). Such haunted mirror lore adds to the general patchwork of psychomanteum-related phenomena, even if not conducted as an intentional session.

To sum up the current state: Psychomanteums straddle the worlds of research, therapy, and ghost hunting, respected fully by none yet intriguing to all. They represent a low-tech, human approach to what high-tech tools and mediums also attempt – bridging the living and the dead, or the conscious and unconscious mind. As of 2025, they remain a niche curiosity. Perhaps in time, they’ll be more widely adopted in grief counseling. Or maybe someone will devise a “smart mirror” for spirit communication that brings the concept into the tech age. For now, the practice remains elegantly simple: a person, a mirror, and a quiet invitation to the unknown.

Ghost caught in mirror at the Sorrel-Weed House, Savannah GA

Reunions by Leigh Davis is a moving and immersive art installation that explores themes of grief, memory, and connection with the dead. Inspired by the ancient and modern practice of the psychomanteum, Davis invites participants into a darkened, quiet space designed for reflective encounter—both with themselves and with the loved ones they’ve lost. Through the careful interplay of environment, ritual, and intention, Reunions becomes more than art—it becomes a vessel for mourning, dialogue, and healing.

You can learn more and experience the project at: leighdavisprojects.com/reunions

Reflections of Life, Death, and Mystery

Our journey through the realm of psychomanteums – from ancient oracles to modern experiments – illuminates a profound human truth: across eras, we have yearned for connection beyond the grave, and we have been endlessly inventive (and persistent) in finding ways to seek it. The mirrored chamber, in all its forms, is a testament to that yearning.

Stand before a mirror and you see yourself. But sit before a mirror in the dark with an open heart, and you just might see more than yourself. This duality captures the essence of the psychomanteum: it is both a psychological mirror and a metaphysical one. It reflects inner truths – our love, our grief, our subconscious imagery – and possibly reflects an outer truth: that the ones we love are not truly gone, only living in a place our ordinary eyes cannot perceive.

Historically, we saw the psychomanteum morph from solemn temple rituals to folk practices to clinical settings. The constant throughout has been the sincerity of intent. Ancient Greeks traveled to Ephyra genuinely seeking wisdom from departed souls. Medieval wizards peered into mirrors seeking knowledge (or power). A grieving parent today may quietly sit in a dark closet with a mirror praying to see a lost child. In each scenario, the mirror is a means to an end – the end of bridging a heartbreaking gap. And even though methods and interpretations differ, that common human thread binds them together.

Reflecting on the journey (pun intended), one cannot help but feel a sense of awe. Awe at the courage of those who venture into dark spaces of uncertainty. Awe at the mind’s capacity to heal itself through visionary experience. Awe at the possibility that maybe, just maybe, some of those visions were exactly what they appeared to be: visits with those we love in a dimension we have yet to chart with science.

The psychomanteum also teaches humility about what we label “real.” Is the comfort John felt after seeing his deceased wife in the mirror any less real because a scientist might call it a hallucination? The tears of joy were real, the change in his life was real. As an investigator and historian, I’ve learned that sometimes the effects of belief are as important as the object of belief. Psychomanteums occupy that liminal space where reality and perception blur – and in that blur, transformative things can happen. It urges us not to be too rigid in dismissing personal experiences simply because they don’t fit conventional models. At the same time, it invites us to apply thoughtful analysis, to appreciate both the power of the mind and, possibly, the power of the spirit.

Standing at the mirror between worlds, one foot in known science and one in mystifying experience, the balanced approach is to neither gullibly accept everything as ghosts nor cynically write it off as tricks. Instead, we marvel. We marvel that a simple mirror, a bit of darkness, and a guiding intention can unlock such depth within us – and perhaps open doors beyond us.

So what do we see, finally, in this mirror metaphor? We see hope. We see a tool that has provided comfort in the face of the greatest fear humanity knows – the loss of loved ones and the mystery of death. We see a practice that, while esoteric, connects to so many familiar human activities (prayer, meditation, remembrance). We see an enduring symbol: the mirror, simultaneously revealing and hiding, reflecting and opening.

In a haunted Savannah attic or a high-tech lab, in a Greek cavern or a suburban bedroom, the act is the same: a person gazes into the unknown seeking an echo back. Sometimes, they receive more than an echo; they get an embrace across eternity.

Whether one uses a psychomanteum for personal solace or out of historical fascination, the experience underscores one beautifully haunting fact – love and longing do not easily accept finality. We will find a way, be it through mirrors or dreams or the rituals of our ancestors, to feel connected. And perhaps in doing so, we keep those we love truly alive, if not in body, then in heart and memory – and maybe even in spirit.

Next time you find yourself alone in front of a mirror, in a quiet moment, don’t be afraid. Think of the generations before who looked at that same reflective surface and dared to ask it for something more. Think of the calm darkness and what it might conceal or reveal. The psychomanteum reminds us that reality has layers: what we see in the daylight is only one layer. Under the right conditions, we might peel back a layer and catch a glimpse of the other side – and see in it not something to fear, but a continuation of the story, a face of someone beloved, smiling back.