In the hush of a long-abandoned ruin, a paranormal investigator presses “Record” on a digital device. Every creak and distant drip seems amplified in the dark. Hours later, upon playback, a faint whisper emerges – a voice that wasn’t heard live. This eerie experience is the essence of Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVPs), a cornerstone of ghost hunting lore.

Table of Contents

Historical Evolution of EVP Research

Famous Case Studies and Their Impact

Scientific vs. Supernatural Debate

Equipment and Techniques for Capturing EVPs

Step-by-Step-Guide-for-an-EVP-Session

Beginner to Advanced Progression

Psychological and Auditory Explanations for EVPs

Auditory Hallucinations vs. Real Phenomena

The Role of Expectation and Desire

Introduction to EVPs

.

Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVPs) are unexplained fragments of sound—often resembling human speech—captured on audio recording devices with no clear natural source at the time of recording. In simpler terms, an EVP might be a mysterious voice or phrase imprinted on tape or digital audio, even though no one (and nothing) present should have produced it. These phantom voices have stirred fascination and fear in equal measure. Imagine hearing a gentle “hello” or your name in a playback, despite having been alone in the room; it’s no wonder EVPs intrigue believers and skeptics alike.

From curiosity-seekers to seasoned paranormal researchers, many are drawn to EVPs because they offer a tantalizing possibility: evidence that perhaps our words and consciousness don’t end with death. For ghost hunters and spiritual believers, an EVP can feel like a muffled greeting from the beyond – a departed loved one reaching out, or a spirit lingering in a haunted hall. The very otherworldliness of EVPs carries an emotional weight. Some find comfort in them, hearing proof of an afterlife, while others feel a chill, as if they’ve opened a door that ought to remain closed. On the flip side, skeptics and scientists are captivated (and often challenged) by EVPs for a different reason: these recordings present a puzzle of perception. Are we truly hearing unseen spirits? Or are these sounds a trick of electronics and the mind? The debate over what EVPs are – genuine paranormal voices, radio interference, or auditory illusions – has fueled research, arguments, and late-night talk show discussions for decades.

What makes EVPs so compelling is this very tension between belief and doubt. One person’s awe-inspiring proof of a ghost may be another person’s misunderstood static. Yet, even the doubtful can’t help but lean in when an investigator plays a particularly clear EVP: a distinct voice responding directly to a question, for example. In those goosebumps-raising moments, the line between the known and the unknown blurs. This article will take you on an immersive journey through that liminal space. We’ll hear stories of early pioneers who first stumbled on these voices, examine famous recordings that defy easy explanation, and dive into the science that tries to explain (or explain away) the phenomenon. Along the way, we’ll stand in dark attics and abandoned hospitals with investigators, feeling the prickling anticipation of a potential otherworldly reply in the silence. And we’ll also step into the lab and the psychology of perception, where researchers dissect how a stray radio signal or the brain’s pattern-seeking might create the illusion of a ghostly whisper.

By the end, you’ll have a rich understanding of EVPs – not just as isolated snippets of sound, but as a human story. It’s a story of wonder and skepticism, of our desire to reach beyond the veil and our equal drive to demystify the darkness. Whether you lean towards believing spirits roam in the static, or towards debunking every last crackle and pop, EVPs invite you to press “Play” and listen closely. The next voice you hear might make your heart race – and whether it’s a ghost or just noise is for you to decide.

Historical Evolution of EVP Research

To truly appreciate EVPs, we must journey back to a time before digital recorders and ghost-hunting TV shows – back to the mid-20th century, when the idea of capturing voices from thin air first took root. The fascination actually traces even further to earlier decades: famed inventor Thomas Edison reportedly wondered if new technology could serve as a telephone to the beyond. Edison never did create his rumored “spirit phone,” but his era’s optimism set the stage for later experiments. By the early 1900s, the Spiritualist movement had entranced many with séances and Ouija boards, and as soon as audio recording devices appeared, intrepid minds began testing if these machines could eavesdrop on the afterlife.

One early trailblazer was Attila von Szalay, an American photographer and ghost enthusiast. In the 1940s, long before EVP was a coined term, von Szalay attempted to capture spirit voices first using a 78 rpm record and later a reel-to-reel tape recorder. Picture him in a small room turned makeshift lab, a microphone placed inside an insulated cabinet, wires snaking out to his recorder. He’d ask questions into the ether and wait. In 1956, to his excitement, von Szalay believed he succeeded – on playback of an apparently silent session, he heard something.

Some of the first alleged EVPs were simple and even whimsical words: “This is G!”, “Hot dog, Art!”, and even a cheery “Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to you all”. These messages, though odd, were interpreted as greetings from beyond. In 1959, von Szalay and a colleague, Raymond Bayless, published an article about these mysterious voices in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, bringing the phenomenon to the attention of other researchers.

While von Szalay was experimenting in America, across the ocean in Sweden a discovery occurred that would truly ignite modern EVP research. Friedrich Jürgenson, a Swedish painter and filmmaker, wasn’t ghost-hunting at all on the fateful day of June 12, 1959. He was outdoors, in a small Swedish village called Mölnbo, recording birdsongs on a portable tape recorder – likely the warm warbling of birds was all he expected to hear on playback. But when Jürgenson played the tape back later, he was stunned to hear a voice that shouldn’t have been there. As the story goes, he recognized it instantly: it was the voice of his deceased mother, speaking in a loving tone, perhaps calling his name. In later recordings, Jürgenson even heard the voice of his late wife. One can imagine him frozen in his chair, replaying the tape over and over, the hair on his arms standing on end as he realized no living person had spoken those words during the recording session.

Encouraged and mystified, Jürgenson delved deeper. Over the following years, he recorded thousands of audiotapes, claiming to document messages not only from personal loved ones but from historical figures as well. Jürgenson approached these recordings almost like an archaeologist of sound, cataloguing voices from an alleged other world. He wrote books about his findings and even theorized on how this communication was possible – proposing at one point a bold idea of a “fourth dimension” of life where these voices resided. His work gained enough attention that professional researchers took note. In the 1960s, he shared his methods with others, including a Latvian psychologist named Konstantin Raudive.

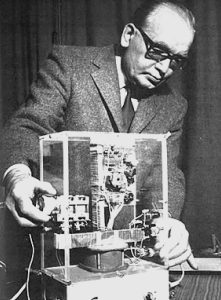

Konstantin Raudive pictured alongside the Goniometer, a specialized instrument developed for him by high-frequency engineer Theodore Rudolph. The Goniometer was among several unique devices Raudive utilized in his pioneering experiments with Electronic Voice Phenomenon (EVP).

If Jürgenson was the discoverer, Konstantin Raudive became the zealous evangelist of EVP. Raudive, fascinated by Jürgenson’s claims, began conducting painstaking experiments. He would sit for hours in a quiet room with a recorder running, sometimes speaking questions into the air in multiple languages (he was fluent in several), other times just leaving tape rolling in silence. By the time of his death in 1974, Raudive had amassed a staggering archive: he made over 100,000 recordings that he believed contained voices of the departed.

To rule out simple radio broadcasts accidentally being picked up, Raudive even conducted sessions in an RF-screened laboratory, shielding the recorder from stray radio waves. Incredibly, he still detected voices. Some were brief utterances, others were just faint mumblings, but many, Raudive claimed, were intelligent responses – answers to his questions or comments on his activities.

The clarity of some voices was such, he argued, that no normal explanation sufficed. In one dramatic experiment, Raudive invited a group of listeners to hear his best recordings and write down what they thought was said. To his satisfaction, many of them independently identified the same phrases, suggesting these sounds truly were coherent voices, not just random noise.

Raudive published a seminal book, Breakthrough: An Amazing Experiment in Electronic Communication with the Dead, in 1968 (translated to English in 1971), which detailed his methods and presented transcripts of many EVP messages. This book spread the EVP phenomenon to a much wider audience. Readers around the world – from engineers to clergy to everyday folks who had lost loved ones – began trying their own hand at capturing EVPs. Throughout the 1970s, the momentum grew. An electronics engineer named William O’Neil even claimed that, via psychic inspiration, he built a device called the Spiricom, essentially an electronically generated tone device that purportedly allowed real-time conversations with spirits. Though O’Neil’s Spiricom results were controversial (and later debunked as likely a result of wishful thinking or perhaps outright fraud), the idea of using custom technology for spirit communication took hold.

Another inventor, Frank Sumption, created in 2002 what is colloquially known as “Frank’s Box” or the Ghost Box. This device swept through AM radio frequencies rapidly, creating a constant wash of white noise and snippets of broadcasts. The theory was that spirits could manipulate this noise to form words in real time. Ghost Boxes are effectively an evolution of EVP tech – instead of recording and analyzing later, investigators could listen live to the chatter of the noise and often interpret replies on the spot. Critics, however, point out that such devices are “a modern version of the Ouija board,” prone to subjective interpretation and the human tendency to find meaning even where none exists. Because Ghost Boxes intentionally scan radio stations, they will inevitably produce random words and syllables; any “meaningful response” might just be coincidence or the listener’s brain stitching fragments together.

By the late 20th century and into the 21st, EVP research truly blossomed into a field – albeit a fringe one – with its own organizations, conferences, and dedicated enthusiasts. In 1982, Sarah Estep founded the American Association of Electronic Voice Phenomena (AA-EVP), aiming to standardize methods and share findings among the community. Estep herself, starting in the 1970s, collected hundreds of EVPs and intriguingly reported some voices that claimed to be not only the dead, but also “extraterrestrials” from other dimensions or planets. The term Instrumental Trans-Communication (ITC) was introduced by researcher Ernst Senkowski to encompass not just voices on tape, but any use of electronic devices to communicate with presumed spirits – including fax, television, and computers. One famous case of ITC involved a television in 1987 seemingly showing the face of the now-deceased Friedrich Jürgenson during a memorial broadcast – as if, for a moment, he reached through the static of a detuned TV to say one final hello.

Through these decades, EVP techniques evolved from analog to digital. In the reel-to-reel days, researchers dealt with magnetic tapes, physical splicing, and the possibility of previous recordings bleeding through due to imperfect erasure (indeed, one hypothesis is that some early EVPs were just faint remnants of earlier recordings on reused tapes). With the advent of portable cassette recorders in the 1980s and then compact digital voice recorders in the late 1990s, capturing EVPs became easier and more accessible than ever. One particular digital recorder model from the 90s – the Panasonic RR-DR60 – achieved near-mythical status among ghost hunters for its apparent knack of picking up ghostly voices that other devices missed. It was dubbed the “Holy Grail” of EVP devices (though skeptics later noted it was likely because the DR60’s internal design was flawed and created noise and false positives, essentially “hearing” voices where none existed due to its own electrical quirks).

By the 2000s, EVPs had firmly entered pop culture. Paranormal investigation TV shows like “Ghost Hunters” and “Ghost Adventures” frequently featured EVPs as dramatic evidence – the team reacting in astonishment to a disembodied voice captured on playback, replaying it with subtitles reading something eerie like “Get out!” or “I’m here.” These scenes, often shot in night vision green, introduced millions to the concept of EVP and inspired a new generation of hobbyists. Today, an EVP session (sitting in a haunted location with a recorder asking questions) is a staple of any ghost tour or amateur investigation. The legacy of Jürgenson, Raudive, and their contemporaries lives on each time someone hits the record button in an empty room and nervously hopes – or fears – to hear something on the other side of silence.

Famous Case Studies and Their Impact

EVPs range from faint and crackling murmurs to startlingly clear phrases. Over the years, some recordings have stood out as especially compelling or chilling, often swinging open the door to new believers or deepening the intrigue for seasoned researchers. Let’s delve into a few famous cases and the impact they’ve had on the field of paranormal investigation and public perception.

One of the earliest celebrated EVPs came, as mentioned, from Friedrich Jürgenson’s work. After his initial 1959 discovery of voices on his bird recordings, Jürgenson produced many notable EVP clips. In one case, he recorded what he interpreted as a message from his late mother advising him on a health issue – deeply personal content that struck him as unlikely to be random radio noise or coincidence. Such intimate EVPs had a profound impact: they shifted the perspective of EVP research from a novelty to something potentially life-changing. Here was not just a curiosity, but possibly a line of communication with those we dearly miss. This encouraged many bereaved individuals to try EVP recording as a form of reaching out – a practice that continues today with people leaving recorders by graves or in bedrooms, hoping for a last loving word from a spouse or child who passed on. It also influenced paranormal researchers to treat EVP sessions with a mix of scientific curiosity and human reverence, knowing how meaningful such an outcome could be.

Friedrich Jürgenson at an international press conference in Mölnbo, Sweden, June 1963.

Moving forward, Konstantin Raudive in the 1960s recorded an extensive catalog of voices, and among these he claimed to have captured some rather famous communicators from beyond the grave. In an astonishing (and controversial) twist, Raudive reported EVPs that he believed were the voices of historical figures. For instance, he asserted that he had recordings featuring the voices of Adolf Hitler and Winston Churchill, each supposedly coming through with brief remarks. Skeptics found this hard to swallow – why would such notable personalities be lingering in Raudive’s lab, and how could one verify it was truly them? Nonetheless, the boldness of the claim drew public attention. It added a sensational flair to EVP lore: the idea that even the great (or infamous) dead might be chatting away in the white noise. While many dismissed those particular claims, they fueled interest and debate. People who might not have paid attention to a muffled “hello” took notice when someone said, “I have Hitler’s ghost on tape.” This, in turn, spurred more researchers to either try to replicate such results or to debunk them, advancing the rigor of experiments.

Perhaps the most famous EVP case to capture mainstream attention in more recent times occurred in January 2007 at an old hotel in upstate New York. The Central New York Ghost Hunters (CNYGH), led by investigator Stacey Jones, conducted an overnight investigation in this reportedly haunted, history-rich hotel. The building had a colorful past – even whispers of mob activity and a brothel during Prohibition – and the team was prepared for something. What they got became known among enthusiasts as one of the most horrific EVPs ever recorded. During the investigation, two female team members and a family member of the owners sat on a staircase to do an EVP session, as they had heard unexplained footsteps and soft voices near that spot earlier. They pressed record on a digital voice recorder and waited in relative quiet, occasionally engaging in light conversation amongst themselves.

When they later reviewed the audio, the quiet chat on the stairs was drowned out by a disturbing auditory scene that none of them heard at the time. On the recording, a violent struggle can be heard playing out: there are sounds of a scuffle, muffled cries, and a panicked male voice repeatedly pleading “Help!”. A cuckoo clock chimes and ticks (though, curiously, there was no cuckoo clock on the premises in reality). Amid the chaos, a woman’s voice is heard angrily saying, “Get off me!” as if fending off an attacker. Meanwhile, the three women on the stairs are oblivious, their live conversation continuing calmly overtop these ghostly echoes of a past event. This EVP runs for an unnervingly long duration – not just a word or two, but almost a narrative of an assault or desperate altercation. Everyone involved was shocked by the playback. All the investigators present were female, yet here was a distinct male voice and evidence of violence that simply hadn’t been audible to them in the moment. The owners were equally stunned, and given the hotel’s rumored history of “nefarious activity,” they wondered if the tape had captured an imprint of a crime long past, somehow locked into the environment and re-playing itself.

This case made waves. It was featured in online paranormal forums, on radio shows, and in an article titled “Listen to One of the Most Convincing EVP Recordings Ever Captured.” For many listeners, the length and visceral detail of the recording were chilling; it wasn’t a leap to imagine that perhaps a traumatic event – perhaps decades ago on that very staircase – had left a psychic residue that the recorder picked up. The impact of this case was two-fold: first, it galvanized investigators to realize EVPs might be more than one- or two-word snippets; under the right conditions, perhaps entire ghostly events could imprint on audio. This has led some teams to conduct longer, more passive recording sessions (just letting the recorder run in an empty room for hours, for instance, in hopes of catching something extensive). Second, it challenged skeptics to explain such a complex recording. Suggestions ranged from hoax (though the CNYGH team swore it was genuine and unaltered) to some freak cross-modulation of a distant radio drama or baby monitor. To date, no definitive normal explanation has been found, leaving it as one of the modern “high strangeness” EVP cases.

Another well-known case happened in the historic Shanley Hotel in Napanoch, New York – a hotbed of reported paranormal activity. During a Ghost Hunters TV investigation, the team captured what sounded like an argument between unseen people in an empty former bordello room of the hotel. On the enhanced playback, listeners made out frantic shouts: “Knock it off… Don’t hurt Anna… Just stop… Frank!”. The names and context seemed to fit the location’s lore: there were stories of a prostitute named Anna and a temperamental client named Frank from the 1920s. The fact that these names possibly emerged in the EVP gave ghost enthusiasts goosebumps – it was as if a slice of the past had been captured on a recorder, two spirits forever re-enacting a desperate confrontation. The impact here was showing how EVPs can sometimes dovetail with historical research. After this aired, many paranormal teams started doing more homework on the places they investigate, so if an EVP yields a name or detail, they can verify if it has any historical resonance. When a match happens – like getting the name of a documented person who died at the site – it adds weight to the interpretation that the voice might indeed be that person’s spirit.

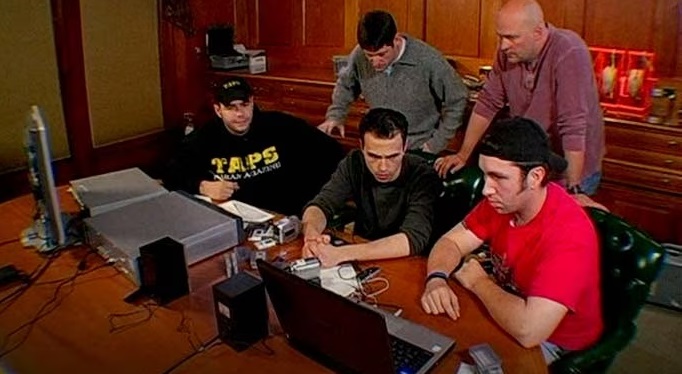

TAPS team from Ghost Hunters reviewing EVP evidence at the Stanley Hotel

Not all influential EVPs are dramatic or intelligible to the public at large. Some are more modest recordings that nevertheless played a big role among researchers. For example, Sarah Estep’s hundreds of EVPs include purported greetings in multiple languages and even odd statements that she thought came from alien entities. While these didn’t make headlines, her meticulous logging of methods (she often noted the conditions under which clearer voices occurred) helped shape investigation techniques and inspired the formation of standardized guidelines for EVP research. Similarly, project Scole (the Scole Experiment) in the late 1990s in the UK – though primarily known for physical medium phenomena – also reported some compelling EVPs during their sessions, further legitimizing the idea of using electronics alongside more traditional séance methods.

Each of these cases, famous or obscure, has contributed pieces to the puzzle that is EVP. They teach investigators what to look for, how to interpret, and sometimes how personal and profound these voices can feel. Additionally, famous cases serve another role: they influence public perception. The more spine-tingling EVPs circulate out in the world via TV or internet, the more people become aware and interested. Ghost hunting groups often cite seeing a case on TV as the spark that got them to pick up a recorder themselves. On the other hand, highly publicized cases also invite critical scrutiny. Skeptical investigators and scientists often choose the most famous EVPs to analyze and attempt to debunk, knowing that if they can explain the big ones, it casts doubt on all the lesser-known ones. Thus, famous EVPs become battlegrounds of a sort – cited in paranormal conferences as evidence of ghosts, and in skeptic conferences as examples of human misinterpretation.

One thing is certain: those who have heard a striking EVP never forget it. Whether it’s an anguished cry from an unknown soul, a polite greeting from a presumed spirit, or a direct answer to a question no living person should have answered, EVPs imprint themselves not just on tape, but on our imaginations. They remind us that the past might not be so silent, and that if we listen closely, we might hear echoes that challenge our understanding of time, memory, and mortality.

Scientific vs. Supernatural Debate

The phenomenon of EVPs sits at a contentious crossroads between science and the supernatural. On one side are those who embrace a paranormal explanation: the voices on tape are exactly what they seem – messages from spirits of the dead, entities from other dimensions, or consciousnesses we cannot normally perceive. On the other side stand the scientific skeptics, armed with knowledge of acoustics, psychology, and radio technology, who argue that EVPs have mundane origins, however uncanny they might sound. To truly understand EVPs, we must examine both sides of this debate and see where we currently stand.

Paranormal Perspectives

Believers in the paranormal origin of EVPs generally assert that some form of intelligent consciousness is manipulating recording devices to imprint voices. The theories vary in flavor:

- Spirits of the deceased: The most common belief is that ghosts – the surviving spirits of humans – are speaking. Perhaps they do so by concentrating their energy to influence the recording medium. The late Oliver Lodge, a pioneer in radio, speculated that the afterlife might exist on a kind of wavelength that technology could someday tune into. In this view, EVPs are essentially modern-day spirit communications, analogous to what a medium might hear or speak in a trance, but imprinted on electronics instead.

- Interdimensional or extraterrestrial communication: Some, like Sarah Estep, have entertained that not all EVPs are human. If consciousness exists beyond our plane, maybe beings from other dimensions or even aliens can use our devices to say hello. These theories arise especially when EVPs contain odd language or concepts beyond a typical ghost saying “boo”. For example, if an EVP voice claims it’s from a planet circling Zeta Reticuli (yes, such things have been reported), those inclined to believe might take it at face value as proof of alien contact.

- Residual energy imprint: A somewhat less “interactive” paranormal theory is that some EVPs are not conscious communication at all, but a kind of psychic echo – moments of strong emotional energy from the past that got imprinted on the environment and play back like a loop. In this theory, when you capture an EVP of, say, a murder victim screaming, it might not be the spirit of the victim actively trying to communicate, but rather a residual imprint of the traumatic event that occasionally becomes audible (perhaps triggered by the presence of recording equipment or the energies of investigators). This idea dovetails with broader ghost lore of “residual hauntings,” where ghosts seem to reenact events without acknowledging the living. The 2007 hotel EVP of a violent struggle could be interpreted this way: a lingering memory of the building itself, caught by the recorder like needle on a phonograph.

Spirit guides or psychokinesis: Some EVP researchers believe they receive assistance from the other side in their recordings – like the concept of a spirit team helping to patch calls through. Others have posited that psychokinesis (mind over matter) by living people could influence recording devices. For instance, a deeply emotional investigator might subconsciously cause the device to record what they want or expect to hear. This edges more into parapsychology: are EVPs voices of external spirits, or projections of our own minds? If the latter, one could still categorize it as paranormal (since it’s beyond conventional science) but not literally ghosts.

The common thread in paranormal theories is the assumption that EVPs involve a communicating intelligence beyond the typical functioning of the equipment. Proponents point to certain features of EVPs they feel are hard to explain otherwise: the way some EVPs seem to respond directly to questions, use personal names or relevant information unknown to others, or occur in multiple languages familiar to the experimenters. They also note how EVPs often go beyond what random radio interference would produce. For example, a random snippet might be a word or two, but sustained, contextually appropriate sentences are less easy to wave off. The paranormal camp often emphasizes open-mindedness – citing that just because we don’t fully understand how spirit communication works, doesn’t mean it’s impossible. After all, radio waves or smartphones would seem magical to someone a few centuries ago; perhaps EVPs are an early glimpse into a new frontier of science connecting consciousness and technology.

Paranormal researchers sometimes invoke concepts from physics, like energy conservation (“the energy of personality might persist after death in some form”) or quantum theory (with its weird non-locality and observer effects) to muse on how voices might imprint on devices. These are largely speculative analogies, but they serve to suggest that known science doesn’t entirely close the door on the possibility. They also highlight that EVP research, in their view, deserves scientific attention precisely because it could reveal new principles about consciousness.

Scientific Explanations

.

On the flip side, scientists and skeptics approach EVPs with the principle of Occam’s Razor – favoring the simplest explanation that requires the fewest assumptions about how the world works. From this view, jumping to ghosts or unknown entities is unnecessary when several well-understood phenomena can account for strange voices on recordings.

Some key natural explanations include:

- Auditory Pareidolia: The human brain is exquisitely tuned to recognize patterns, especially speech, even in random noise. Pareidolia is typically known in visual form (seeing faces in clouds or the Man in the Moon). Auditory pareidolia is the equivalent with sound – the brain tries to make sense of random noise and often “hears” words or music in the static. If you’ve ever been half-asleep with a fan running and thought you heard the phone ring or someone call your name, that’s a mild form of this. With EVPs, researchers like psychologist Joe Banks have described the effect as “Rorschach Audio,” meaning the sounds are like an inkblot test – you might interpret them according to your expectations. An interesting supporting observation: EVP voices are almost always in a language the investigator understands, rarely a foreign tongue. If spirits of all nationalities abound, you’d think you’d sometimes capture languages you don’t speak. The fact that EVPs tend to “speak” the same language as the listener hints that the listener’s brain may be a big part of the equation.

- Expectation and Priming: Our expectations can literally shape what we perceive. If someone conducting an EVP session dearly hopes or expects to hear, say, their mother’s voice, they might be predisposed to find a semblance of it in the noise. Likewise, if a ghost hunter tells their team “We got an answer, it says ‘I’m here’ – listen!” everyone will likely hear “I’m here” on the replay. This is why a critical practice (even among serious EVP believers) is to play a suspected EVP clip to fresh ears without telling them what you hear, to see if they independently match your interpretation. Often, if five people get five different impressions of what the EVP voice is saying, it suggests it’s more an illusion than clear speech. A real-life example: at a museum in West Virginia, an investigator recorded what the team believed was the ghost in a portrait saying her name, “Annie.” However, skeptics like Kenny Biddle pointed out that because the name “Annie” was written on the portrait, everyone was primed to hear Annie in the static, and in fact noises that could be fragments of common words (“…and he…”) easily get misheard as “Annie” if you’re expecting it. This priming effect is powerful – in experiments, simply telling listeners to expect a certain phrase greatly increases the likelihood they report hearing it in otherwise indecipherable audio.

- Cross-modulation and Radio Interference: The airwaves around us carry a cacophony of signals – AM/FM radio, TV broadcasts, walkie-talkies, cell phones, baby monitors, shortwave, CB radio, etc. Sometimes, audio recorders or their components (microphone cables, internal circuits) can accidentally pick up snippets of these transmissions. This is especially true for devices with poor shielding or those that use RLC circuits that can resonate with ambient radio waves. A famous old example is that some people used to hear radio broadcasts through their tooth fillings – a quirky case of the metal filling acting as a detector. Likewise, an EVP recorder might grab a word from a far-off CB radio conversation if conditions are right. Sporadic meteor reflections can even bounce distant radio signals briefly into your receiver, a known effect where meteors create ionized trails that reflect radio waves from transmitters beyond the horizon. So that inexplicable foreign-language phrase on your EVP? It might literally be a foreign radio station briefly skipping into your recorder via a meteor’s path – a neat but non-paranormal trick of physics. Serious EVP researchers try to mitigate this by using recording setups inside Faraday cages or deep underground to block radio, and indeed Raudive’s lab tests in a shielded room were an attempt at just that. Still, skeptics note that most ghost hunters operate without such precautions, so stray signals remain a plausible contamination for many EVP clips.

- Equipment Artifacts and Noise: Recording devices themselves produce noise – the quiet hiss you hear if you crank up a speaker with nothing playing. Ghost hunters often intentionally increase their device’s gain (sensitivity) or use high-sensitivity settings to capture very soft sounds. By doing so, they raise the noise floor – the ambient electrical noise level. Within that enhanced noise, the ear can imagine patterns. Additionally, applying filters to audio can introduce weird effects. A researcher named David Federlein pointed out that sweeping filters can make whooshing vowel-like sounds that mimic human speech, not unlike the effect of a guitar wah-wah pedal which creates vocal-like tones. Thus, when ghost hunters filter their recordings to boost clarity, they might inadvertently be creating illusionary voices. Over-boosting certain frequencies or using heavy noise reduction can cause digital artifacts that sound like whispery voices.

- Human Error and Hoaxes: And of course, there’s the baseline explanation that some EVPs are simply mistakes or even fakes. Investigators might not realize someone’s stomach growl or a team member whispering “excuse me” was caught on tape, and later present it as a ghost. This is why good practice is to tag noises in real time – e.g., if your shoe scrapes or you cough while recording, say out loud “that was me” so it’s on record. As for hoaxes, while most EVP enthusiasts are earnest, there have been cases where individuals intentionally added a voice to a clip to spook others or to claim glory. In the age of digital editing, it’s possible to dub a fake “ghost voice” in post-production without obvious seams. Skeptics caution that extraordinary EVP claims should be vetted for such possibilities.

Scientific investigators have put these explanations to the test. For example, psychologist James Alcock analyzed many EVP cases and concluded that “Electronic Voice Phenomena are the products of hope and expectation; the claims wither away under the light of scientific scrutiny.” According to Alcock, things like apophenia – the tendency to find meaningful connections in randomness – and wishful thinking are sufficient to explain what people hear. Indeed, apophenia is a broader concept related to pareidolia; it’s finding significance in randomness, which certainly applies if one is convinced a random blur of static is actually grandpa giving life advice.

Moreover, skeptics like Michael Shermer and Chris French have participated in controlled experiments. In one such experiment, researchers played subjects recordings that were mostly noise but had some ambiguous sounds, telling one group that these were recorded in a haunted location and another group that they were just random noise. The group primed with the haunted narrative reported hearing voices far more frequently than the control group. This demonstrated the powerful role of contextual priming: if you expect a ghost, you’re much more likely to perceive one.

Where the Debate Stands

So, are EVPs voices of the dead or auditory illusions? The truth, as of now, is that the debate remains unresolved in the mainstream. The majority of the scientific community leans towards skepticism, noting that despite decades of attempts, there’s no definitive, reproducible proof that EVPs are communications from beyond. No EVP has ever contained information that irrefutably couldn’t have come through normal means (for instance, a truly unknown fact that is later verified, delivered via EVP, would be a game-changer – but such a case hasn’t been documented to scientific standards).

Organizations devoted to anomalistic psychology (the study of psychological factors behind paranormal beliefs) consider EVPs a prime example of how humans can be fooled by perception. They often demonstrate the effect by playing back “EVP-like” noise and showing how suggestion changes what people hear. From the skeptic viewpoint, every facet of EVPs can be duplicated or explained with non-supernatural methods – and until a recording emerges that defies all such explanations under controlled conditions, they remain unconvinced.

However, EVP enthusiasts point out that just because something can be explained naturally doesn’t mean a particular instance was natural. They argue for continued research, ideally collaborating with unbiased experts, to rule out all normal causes. They also emphasize the personal experiences that often accompany EVPs – the meaningful coincidences, the context (like an EVP that answers a very specific question or says a nickname only a particular deceased person would know). Personal anecdotes aren’t scientific proof, but they are persuasive to those who experience them.

Interestingly, a middle-ground view has also emerged among some investigators: they acknowledge most EVPs might be false positives and psychological, but they hold out that a small percentage could be genuine anomalies worth investigating. These investigators apply more stringent protocols to weed out the easy-to-explain bits (ignoring Class C garble, for instance, and focusing on the rare Class A clear voice that appeared under highly controlled circumstances).

In summary, the supernatural camp sees EVPs as an exciting frontier indicating we survive bodily death in some form, whereas the scientific camp largely sees EVPs as a misinterpretation – a mix of technological quirks and human imagination. The debate thrives in books, conferences, and now on internet forums and YouTube channels where audio clips are shared and picked apart. As technology improves and knowledge grows, the hope (on both sides) is that we’ll inch closer to a definitive answer. Until then, EVPs remain a kind of acoustic Rorschach test: believers hear affirmations of an unseen world, skeptics hear the clever echo of our own minds. And in that contrast, EVPs continue to fascinate – because either possibility, a universe with ghosts or a brain that conjures them from noise, tells us something profound about ourselves.

Equipment and Techniques for Capturing EVPs

If you’ve ever been intrigued to try capturing an EVP yourself – or wonder how the pros do it – this section is your practical guide. Over the years, ghost hunters have developed a toolkit of equipment and refined techniques to maximize the chances of recording EVPs while minimizing false alarms. Whether you’re a curious beginner or a seasoned researcher looking to up your game, it’s crucial to know not just what gear to use, but how to use it properly. Let’s gear up!

Essential EVP Equipment

- Digital Voice Recorder: The workhorse of EVP hunting. Modern digital recorders are small, relatively inexpensive, and very sensitive. They record to memory (no hiss of tape, though sometimes a little internal noise). Many investigators favor simple voice recorders that have a good signal-to-noise ratio and allow USB transfer to a computer. When choosing one, look for models noted for picking up a wide frequency range and having a low noise floor. Some ghost hunters still use old cassette recorders or even reel-to-reel decks, believing analog might capture something digital misses. However, digital is far more convenient and arguably more reliable. A famed device, the Panasonic RR-DR60, is touted by some as unparalleled in capturing EVPs (likely due to its extreme sensitivity and, skeptics note, its tendency to generate a lot of random noise). In truth, you don’t need a rare recorder – any quality recorder will do. Even smartphones have voice recorder apps that can serve in a pinch, though dedicated devices often perform better in low-noise conditions (plus, you want to avoid notifications or interference from the phone’s radio signals, so airplane mode is a must if used). Tip: Use the highest quality setting (HQ or PCM/WAV format) on your recorder so that the audio is not heavily compressed; you want all the detail you can get.

- External Microphone (Optional): Some investigators plug in an external mic to their recorder to improve quality. A good omnidirectional mic can capture sound from all directions, useful in environments where you’re not sure where a voice might emanate. Others use binaural microphones – special dual mics placed like human ears – to get a 3D stereo soundscape. This can help later in determining the direction or source of a sound (and they produce wonderfully immersive audio). If you use a mic, also use a wind screen (the foam cover) even indoors, to reduce wind or breath noises which can sound like whispers.

- White Noise Generator / Spirit Box (Optional): As discussed earlier, some EVP methodologies involve providing a noise source that spirits supposedly use to form speech. A simple method is tuning a radio to static. Devices like Frank’s Box or modern spirit boxes rapidly scan frequencies producing a choppy noise. Use these if you are experimenting with “real-time EVPs,” but be cautious: they will spit out plenty of random words from radio stations. Many EVP purists actually avoid these, preferring the clarity of true silent-room recordings to avoid false positives. A middle-ground tool is a soft noise source like a fan or a specially made EVPmaker software that generates random bits of speech-like tones; these can be used as raw material for possible spirit manipulation. Such techniques are part of Instrumental Trans-Communication (ITC) at large.

- Headphones: A good comfortable set of headphones is critical for review, but some investigators also wear headphones during sessions, especially if doing live listening. Live listening means you have the recorder’s mic feeding directly to your headphones (some devices have this monitor function or you can use a small preamp). This way, you might actually hear an EVP as it happens, even if it’s too quiet for unaided ears. It can be spooky to hear a disembodied whisper in your ears in real time! Generally, for review, over-ear headphones that block external sound are best, so you can focus on the recording details. Earbuds can work too.

- Audio Editing Software: After recording, you’ll likely use software to analyze the file. Programs like Audacity (free) or paid ones like Adobe Audition, GoldWave, etc., allow you to visualize the waveform, amplify sections, filter out background noise, and loop segments. Audacity is popular in the community for its accessibility. It also lets you generate spectrograms – visual representations of sound frequencies – which sometimes help spot anomalies (like a voice might show human-like formants on the spectrogram). That said, any editing (especially noise reduction or filtering) should be done carefully to avoid introducing artifacts that can mislead. It’s often wise to keep an original copy of the raw recording untouched, and make copies for any processing.

- Other Gadgets: Many ghost hunters bring additional gear: EMF meters (to detect spikes in electromagnetic fields that some correlate with ghost presence), thermometers or thermal cameras (for cold spots), and video cameras. While these aren’t for capturing EVPs per se, video cameras often have audio too – occasionally an EVP is caught on a camcorder audio track when the separate recorder got nothing. Having multiple devices can be a form of validation: if an unexplained voice is on both the voice recorder and the camera audio, it rules out some device-specific glitch. Some teams set up multiple recorders in a room’s different corners; if a voice shows up on only one recorder and not the others, it might indicate the sound was very local (perhaps a true EVP right near one device) – or conversely, could mean it was just that device’s quirk. Redundancy is data in EVP work.

Step-by-Step Guide for an EVP Session

So, you have your equipment ready – how do you conduct an EVP session? It’s not as simple as hit record and hope for the best (though sometimes that works!). Here’s a step-by-step approach combining beginner basics with some advanced tips:

- Choose a Location: Ideally, a place with a reputation for activity or that has personal significance. It could be a notorious haunted prison, a historic battlefield, or your own home if you’ve experienced odd occurrences. Wherever it is, try to learn a bit about it: names of people associated, events that took place. This can guide your questions. Ensure you have permission to be there, and never trespass for the sake of ghost hunting.

- Timing and Ambiance: Many prefer doing EVP sessions at night – partly for the spooky vibe, partly because nights are generally quieter (less traffic noise outside, fewer people around). It’s not strictly necessary; EVPs can occur any time, but you do want as much quiet as possible. Some investigators observe that locations “settle” late at night or early hours. Also, if you’re in a public place like a museum, night is the only time you might have silence.

- Set Up Your Recorder: If your recorder has settings, use the highest quality (often called HQ or 192kbps MP3 or, best, WAV format). Disable any voice activation feature (you want it recording constantly, not trying to be smart and cutting out silence, which could chop an EVP). If possible, use fresh batteries and have spares – EVPs won’t happen if your device dies mid-session (and interestingly, paranormal lore says ghosts drain batteries, so keep an eye on battery levels!). Place the recorder on a stable surface or tripod; avoid holding it in your hand, as the mic can pick up your fingers moving or any rustle.

- Silence and Control Noise: Before you start, do an environmental sound check. Note any steady noises – a distant highway, a fridge hum, etc. Try to eliminate obvious ones: turn off that AC unit or fan if you can (unless you’re doing a white noise method). The quieter the room, the better. Absolutely forbid whispering among participants. It’s natural to instinctively whisper in a dark “haunted” place, but later that whisper might be mistaken for an EVP. Speak in normal voice if you must talk. Ideally, remain still; shuffling feet or chairs can sound surprisingly like voices on tape. Tag external noises as they happen (“car passing by,” “stomach growl” etc.) so later you know they were real not paranormal.

- Begin Recording and Introduction: Hit record, then clearly state aloud the date, time, location, and the people present. For instance: “This is April 10, 2025, 10:15 PM, in the attic of the Old Smith House. Investigators present are John and Jane.” This is not only for your records, but sometimes EVPs have been known to oddly comment (“there are three of us…” a ghost voice might add). Also, by stating your identities, any friendly spirits know who they’re “talking” to.

- Ask Questions and Pause: In a normal tone, begin asking open-ended questions. Leave a decent gap of silence after each – usually at least 10 seconds, sometimes more. This gives time for any entity to respond and ensures you won’t overlap the answer with your next question. Common questions: “Is anyone here with us?”, “Can you tell us your name?”, “Do you have a message for us?”, or specific ones like “I read about a person named Sarah who lived here – is Sarah here?”. You can also encourage them: “You can speak into this device I’m holding, and I might be able to hear you.” Keep questions simple and one at a time (don’t ask a string in one breath). Some investigators even converse casually among themselves on purpose, because there’s an anecdotal trend that EVPs sometimes interject comments if you ignore them. For instance, two researchers chatting may later find a ghost voice saying “Don’t mind me” or “That’s funny” responding to their conversation. So feel free to mix direct questions with periods of casual talk or even jokes – just note for the record if a noise happened during it.

- Mind Your Emotions and Approach: Be respectful. Many EVP practitioners treat it like a conversation with present though invisible people. If you’re in a murder scene, you wouldn’t yell “Show yourself, coward!” to a living person (hopefully), so don’t do it to spirits either. Some investigators provoke on TV for drama, but that can lead to a noisy environment (yelling) and if spirits are real, perhaps not endear them to answer. Approach with a calm, inviting demeanor. On the flip side, also maintain healthy skepticism in the moment. If your partner’s chair squeaked, don’t automatically gasp “I heard a ghost!” – acknowledge likely sources.

- Be Aware of Ambient Sounds: As recording proceeds, stay alert. If you think you hear a voice with your own ears, definitely mark the time or say out loud “I just heard a voice” so you can check that spot in the audio. Interestingly, EVPs are often not heard live, only on playback, but occasionally investigators do hear disembodied voices at the time (these are sometimes called Direct Voice Phenomena, a different but related thing). Also note any sudden environment changes (a breeze, a feeling) – while subjective, these notes can later correlate with an EVP (“I felt a chill right before the voice”).

- Closing the Session: After you’ve asked all your questions or feel you’ve spent enough time (sessions can range from a quick 5 minutes to an hour; beyond that fatigue and noise can creep in), thank any entities for their time. Some like to formally say “We’re ending the session now.” Then stop the recording. This delineation helps when you later review multiple files, and if you’re moving to a new location, you’ll start a fresh file.

- Initial Playback on Site (Optional): Some investigators quickly play back the recording on the spot using the recorder’s speaker or headphones. Often the built-in speaker is tiny and may not reveal much. Headphones are better. Doing a quick check can be gratifying if you catch something (“Oh wow, after we asked about Sarah, there’s a voice!”). It also can inform your next steps – if you got a clear “Leave me alone,” maybe you’d stop for the night or try to address the concern. However, the small recorder’s interface is limited for detailed analysis. Many prefer to wait and do a thorough review on a computer later. If you do hear something odd on site, consider doing another session right away to follow up (“We heard what sounded like a reply, can you clarify that?”).

- Download and Save Files: Once home (or back to base), transfer the audio files to a computer. Keep them organized – use filenames with location and date (the suggestion “asylum-1-23-11-10pm.wav” format is great). Back them up; you don’t want to lose that one amazing EVP to a hard drive crash.

- Analytical Listening: Here’s where patience is key. Use your audio software to listen through carefully. Use headphones to catch subtle sounds. You may need to boost volume on very quiet parts. One approach is to watch the waveform: look for any blips in the silence when you weren’t speaking – those could be EVPs. Mark timestamps of anything unusual. Expect that 99% of your recording may just be dead air or normal noise. But that 1%, if present, is the gold. When you find a potential EVP, loop it and listen repeatedly. Try not to immediately assign words; just note “sounds like a voice” at first.

- Enhancing Carefully: If an excerpt is very hard to hear, you can amplify it or apply noise reduction. Be cautious – overdoing it can create illusions. A light touch of filtering can bring a whisper into clarity where you can at least make it out. Some EVP researchers also slow down or speed up clips if they suspect an EVP is too fast or slow to be natural. This sometimes helps in deciphering. Keep copies of the raw vs. enhanced to compare. If you need to present it to others, it’s good to have a cleaned-up version and the original for credibility.

- Seek Second Opinions: As mentioned, once you think you know what the EVP voice is saying, have others listen without telling them your interpretation. See if they independently arrive at the same words. If five people hear five things, the clip might be too ambiguous to count as evidence. If most hear, “It’s Mike,” then you likely have a consensus Class A or B EVP. Note differing opinions in your log. It’s quite common to mis-hear syllables; group analysis can either solidify a finding or debunk a pseudo-voice (sometimes someone will point out, “That’s just the chair creak, not a voice, listen again,” and you realize they’re right).

- Log and Catalog: Maintain a log of your sessions. Document the date, location, who was present, and what (if anything) was captured. For each EVP you believe you caught, note the timestamp in the file and what the interpretations are. This helps later if you compile evidence or revisit a location. It’s also useful for identifying patterns (maybe you notice the same voice comes through at multiple sessions, or certain questions never get a response while others often do).

- Be Honest and Objective: It’s exciting to think you got something, but maintain a level head. If an EVP is faint and could easily be a random noise, mark it as “possible” rather than definite. Never falsify or exaggerate results – integrity is key in this fringe field. It’s better to have a couple of really solid EVPs than a list of maybes. And if someone offers a normal explanation for your EVP that you hadn’t considered, weigh it without ego. We all can be fooled or make mistakes. The goal is truth, not convincing ourselves of a haunting that isn’t there.

- Repeat and Experiment: Often, you won’t get any EVP on a first try. Don’t be discouraged. Seasoned researchers note that perseverance pays off – you might try five times and get nothing and then on the sixth, you capture a gem. Some individuals seem to have better “luck” than others; why is unknown (maybe a psychic element, or just patience and technique). Try different approaches: leaving the recorder running unattended in a room (just remember, you won’t be there to tag noises, so that’s trade-off), using trigger objects (toys, photos that might evoke a response), or asking questions in different languages if appropriate (sometimes a site might have had people who spoke a different tongue).

- Advanced Techniques: For those more experienced, you can experiment with two-way communication sessions. For instance, some investigators use two recorders – one they speak into with questions, and another set a bit farther recording the room sound – to see if the EVP voice might appear on one but not the other (there have been cases where a ghost voice was only on the secondary recorder, fueling the idea it wasn’t audible to the main one or the investigators). Others experiment by running audio through software that attempts real-time analysis (some ghost hunting software will live display if it detects a voice pattern). These can be gimmicky, but technology is evolving.

- Avoid Common Pitfalls: Don’t chase every anomaly. If you spend an hour obsessing if that distant car horn was a ghost moan, you’ll drive yourself crazy. Learn to identify common sounds: a moving footstep can create a soft “uh” sound; cloth rubbing a mic can sound like a sigh. Familiarize yourself with your equipment’s noises (some recorders, for example, have an occasional tick or pop as they write to memory). As noted earlier, absolutely no whispering during sessions – so many “EVPs” online have later been debunked as the investigators themselves unintentionally whispering “let’s go” or such and forgetting. Similarly, don’t talk over each other. If Person A is asking a question, Person B should not suddenly say “oh I felt something” at the same time – you’ve now overlapped any potential answer. Discipline in sessions is key.

Environmental Control: If possible, have a control recorder outside the investigation area. For example, if you’re doing an EVP session in a house, leave another recorder outside on the porch. If later you hear a faint “yes” that you think is a ghost, but the outside recorder also picked up a faint “yes,” you might deduce it was actually a far-off real person or radio that both recorders caught. The outside unit can capture baseline noises (like distant dogs, passing cars) that you might not remember or notice in the moment.

Beginner to Advanced Progression

If you’re a beginner, start simple: one recorder, a quiet room, short sessions, basic questions. The first time you play back and think you hear something, it will be a thrilling moment. But be prepared that many sessions yield nothing obvious. Take that as a baseline – no news is good news, some say, meaning you didn’t accidentally record your own noises at least.

As you become an advanced practitioner, you might assemble an array of gear: multiple recorders, higher-end microphones, full-spectrum cameras to correlate any visual anomalies with audio ones, etc. You’ll also develop a personal style. Some people start every session with a prayer or positive intent, both to invite kind spirits and to protect themselves spiritually. Others keep it very clinical. Find what works for you and what you’re comfortable with. Just maintain the practices that reduce false positives.

One thing both novices and veterans must always keep in mind is the importance of documentation and context. An EVP on its own is interesting, but an EVP combined with witness observations (“At 2:03 AM John and I heard a strange buzz and felt cold, and at that exact time the recorder caught a voice saying ‘cold’”) is much more compelling. So treat each investigation like a scientific field experiment – take notes, state observations, mark times.

Finally, remember to enjoy the process. The pursuit of EVPs can be tedious (hours of quiet, hours of listening to static), but it’s also akin to a treasure hunt or fishing: moments of calm and patience, punctuated by the excitement of a catch. And sometimes, just the atmosphere of doing it – sitting in a reputedly haunted location, asking questions into darkness – can be an unforgettable experience in itself, whether or not a ghost decides to talk back.

Psychological and Auditory Explanations for EVPs

We touched on the science versus spirit debate earlier, but let’s delve deeper into the fascinating workings of the human brain and auditory perception that play a huge role in the EVP phenomenon. Even if one remains open to EVPs being paranormal, it’s undeniable that psychology influences what we think we hear. Understanding these cognitive and sensory factors not only helps in analyzing EVPs more critically, but it also offers insight into how our brains make sense of the world – sometimes creatively so.

The Human Brain on Sound

Our ability to interpret sound, particularly speech, is a marvel of evolution. The brain has specialized regions (like Wernicke’s area) devoted to processing language. It’s wired to detect patterns and familiar structures (like syllables and words) extremely quickly, even in noisy conditions. This is why you can often understand your friend in a loud restaurant – your brain zeroes in on the expected patterns of speech.

However, this talent can be a double-edged sword. The brain will sometimes perceive words where none exist, simply because the incoming sounds resemble speech in some way. This is the root of auditory pareidolia. For example, think of when you play a song in reverse (as some conspiracy enthusiasts used to do looking for “satanic backmasking” in rock music) – most of it is gibberish, but occasionally you might hear a phrase like “I am here” emerge from the reversed syllables. There’s no actual hidden message; it’s your brain imposing order on chaos.

There’s also the phenomenon of misheard lyrics, often called mondegreens. You might have had the experience of singing along confidently to a song only to later learn the real lyrics are different. Classic case: Many people heard “Hold me closer, Tony Danza” instead of Elton John’s “Hold me closer, tiny dancer.” The sounds are similar, and if Tony Danza is a familiar name in your brain, it happily slots that in. With EVPs, especially those Class B or C ones that are fuzzy, our brains do the same – grasping at the closest match in our mental dictionary of sounds. One investigator humorously noted that an EVP sounded to him like “Lucy in the sky with diamonds” which his colleague heard as “Lucy likes to fly on diapers,” highlighting how without a clear reference, our brains fill blanks often absurdly. In ghost hunting, no one expects diapers or Tony Danza to come up, but if an investigator’s mind is on, say, “Is there a ghost here?”, then a vague “ssssHere” might be mentally completed to “I’m here.”

Our brains are also influenced by recent memory and context. If you just asked “What is your name?”, your brain is actively primed to hear a name in response. So if a burst of static has a pattern that could be interpreted as a name, you’re much more likely to latch onto that. In one experiment, participants listened to EVP-like sounds after being given either a paranormal context or a neutral context. Those primed with the idea of ghosts reported significantly more voices and often “heard” words consistent with the ghost story given.

There’s also a survival or social aspect: humans hate not understanding voices. It’s almost an anxiety – think of how you strain to hear someone when you catch just a whisper of sound. We’re compelled to resolve uncertainty in what we hear, because in our ancestral past, hearing a voice or sound could mean a friend, foe, or danger calling. So a faint ambiguous sound doesn’t stay ambiguous for long; the brain will decide on a “best fit” interpretation quickly and often stick with it stubbornly.

Auditory Hallucinations vs. Real Phenomena

An auditory hallucination is hearing something that isn’t actually present. Now, in EVP cases, the recording does have a sound, so it’s not a hallucination to hear a sound; rather the question is the interpretation of that sound. True auditory hallucination (like in certain mental illnesses or under drug influence) is a different beast – that’s hearing voices with your ears when there’s no sound wave at all. However, there is a subtle crossover: when someone deeply involved in EVP analysis listens to hours of noise, they might start to imagine voices in the noise even when not playing it. Sensory deprivation or monotonous stimulus can cause the brain to generate patterns (like people in anechoic chambers – extremely silent rooms – often begin hearing phantom whispers or beats).

For EVP analysis, the risk is more about illusion than hallucination. Think of the famous “Laurel vs. Yanny” audio clip that went viral. Some people heard the name Laurel, others distinctly heard Yanny, from the same recording. It turned out that both sets of sounds were present in different frequencies and what you heard depended on your hearing curve and what frequencies your device emphasized. It was a great example of how subjective hearing can be – two intelligent, normal-hearing people can honestly hear completely different words. In EVP, many clips are much less clear than Laurel/Yanny. So it’s entirely plausible for one person to sincerely hear a pleading “help us” and another hears a garbled “elephants,” and a third hears nothing at all but a squeak. Auditory perception is a mix of the ears (the hardware) and the brain (the software), and both vary from person to person.

EVP enthusiasts might argue: if multiple people independently hear the same phrase, doesn’t that validate it’s really there? It can, especially if the people aren’t influencing each other. But one must consider group biases – often one lead investigator says “It says X, do you hear it?” and then everyone hears X. Independent listening tests, as we mentioned, are thus crucial. In some notable cases, e.g., the Raudive experiments where he played his EVPs to listeners, there was significant agreement on certain words. That suggests those particular EVPs had enough clarity or distinctive sound pattern to produce a consensus – which in turn suggests if an EVP reaches that level, maybe it truly is an objective sound (still could be stray radio, but at least not purely imagination).

The Role of Expectation and Desire

Imagine sitting in a dark, reputedly haunted house with your recorder running. You want something to happen – even if it’s just to validate the effort you’re putting in, or to experience that thrill of contact. This desire can color your perceptions. This is what James Alcock meant when he said EVPs often are products of hope and expectation. It doesn’t mean people intentionally fake it; it means their very hopeful mindset makes them interpret ambiguous stimuli in a way that aligns with their hopes (i.e., that ghosts are talking). It’s a kind of confirmation bias – you pay attention to hits and overlook misses. If you ask 50 questions and on one of them you think you got a relevant answer, you might focus on that one “success” and disregard the 49 silences or nonsense blips as just the ghosts being selectively talkative.

Cognitive dissonance also plays a part. If someone spends hours and believes they got an EVP, they become invested in it. Being told it’s just noise can cause mental dissonance (“Did I waste my time? Am I foolish?”). To resolve that, they may double-down on believing it’s real. This is common in many fields, not just ghost hunting – once we think we have an interesting result, our ego gets involved.

The psychological aspect also extends to fear and the spooky ambiance of investigations. In a frightening setting, adrenaline is high. Sounds get perceived as more significant than they might be in a calm setting. A faint tap in your brightly lit kitchen might go unnoticed, but the same tap in a dark abandoned asylum might make your heart skip and your brain go “Was that a voice?!” This is our fight-or-flight response on a hair trigger. Ghost hunters try to keep calm, but no one is immune to a little creep-out in a dungeon or attic at 3 AM. Managing fear is part of the technique; otherwise, you risk “hearing things” not because a ghost spoke, but because your own nerves are shouting.

Group Dynamics and Suggestion

If you’re investigating with others, be aware of group psychology. Humans are social creatures; if one person with authority or confidence asserts an interpretation (“I definitely heard ‘Get out’!”), others are likely to concur or at least second-guess their own senses. This can create a kind of feedback loop of belief. There’s a documented effect where people in groups will conform to a majority opinion on what they heard or saw, even if it’s wrong, to avoid conflict or the feeling of being “the odd one out.” Good investigative teams encourage members to speak up with alternate opinions (“Actually, I hear something different…”) to mitigate this.

There have been fun experiments at ghost hunting events where the organizers plant a suggestion: for example, telling participants beforehand, “Many people hear a little girl singing in this room.” During the EVP session, none such sound actually occurs, but lo and behold, some participants later claim they heard the little girl – their expectation conjured it in their mind or made them misinterpret a distant bird or a car brake squeal as a “singing child”.

This is not to say every EVP is imagined. But it highlights the need for controlled conditions and skeptical thinking even among believers. Some paranormal teams actually include a designated skeptic on the team whose job is to provide alternate explanations and curb enthusiasm from running away. By being aware of these psychological tendencies, investigators can better guard against them: by remaining neutral in the moment (“We got something at 3:15, noted” instead of “This is grandma talking!”), by doing blind reviews, and by training themselves to consider multiple hypotheses for any sound.

The Fun of Audio Illusions

To lighten the mood a bit: the world of audio perception is full of neat illusions that show how our brain can be tricked. One example is the Phantom Words Illusion – where two syllables played over each other can make you “hear” all sorts of phrases after a while. Another is the Shepard Tone – a sound that seems to forever ascend in pitch but actually isn’t (less about words, more about perception). There are also backmasking illusions where reversed speech is perceived as forward speech with meaning (again, thanks to pareidolia).

Why mention these? Because they illustrate that our senses are not infallible recorders of reality; they are interpreters. And EVPs live in that gap between raw sound and interpreted sound. Some serious researchers, like Anomalistic psychologist Chris French, use examples of such illusions when lecturing about EVPs to make audiences realize: “If your brain can hear a full sentence in gibberish when prompted, then hearing a sentence in a staticky EVP is not so extraordinary after all – it might just be your brain doing what it always does.”

It’s also worth noting how memory plays a role. If you’ve decided an EVP says a particular phrase, every time you listen, you reinforce that memory. Soon you cannot hear it any other way (just as once you know the actual lyric of a song, you can’t remember how you ever misheard it). This means once an interpretation is set in your mind, it’s very hard to shake, even if wrong. That’s why first impressions in analysis are important to question, and why sharing with peers is helpful to break any personal cognitive lock.

Rational Mind, Open Mind

From a psychological perspective, a good EVP investigator is a bit of a paradox: you need an open mind (to accept that something odd might be occurring beyond known science) but also a rational, critical mind (to filter out the many ways your own senses and brain might fool you). Balancing these is crucial. Lean too far skeptical and you might dismiss a genuine anomaly; lean too far credulous and you’ll think every stomach gurgle is a ghost.

Some researchers approach EVP sessions almost like a mindfulness exercise – keeping calm, detached, making observations without judgment (“I hear a sound at 10 seconds, could be something”). This more zen approach can help prevent your expectations from running wild.

In conclusion, the psychology of EVPs teaches us humility. It shows that hearing is not believing, necessarily. It also highlights why EVPs are so personal. One person’s profound afterlife evidence might leave another person scratching their head, hearing nothing of the sort. Understanding the role of perception doesn’t negate the possibility of real EVPs, but it ensures that if we are to claim “this is an anomalous voice,” we’ve ruled out the rich arsenal of tricks our senses might be playing on us. And if nothing else, exploring these auditory quirks is fascinating in its own right – it’s like a window into the brain’s language center, watching it try its best to make meaning out of mystery.

EVP Analysis and Verification

Capturing an EVP is just the first half of the journey; what comes after – analysis and verification – determines whether that eerie whisper becomes a piece of credible evidence or gets dismissed as a stray noise. This section will walk through how investigators dissect their recordings, what tools they use to separate true voices from false positives, and how to build a case that an EVP is genuine. We’ll also examine the informal classification system for EVPs and the challenges of proving a voice is really from the beyond.

The EVP Classification (Class A, B, C)

Within the ghost hunting community, EVPs are often categorized by clarity:

- Class A EVP: Loud and clear, easily understood by almost anyone without need for enhancement or prompting. These are the crown jewels – you press play and everyone in the room hears “Help me” or “I am Peter” distinctly. A Class A can be copied, shared, and people will generally agree on what’s said. They’re rare. If you have even a couple of Class As in a long career, that’s notable.

- Class B EVP: A bit faint or muffled – you can tell it’s a voice and make out some of it, but it might require headphone listening or a couple of replays to discern. Different listeners might have slightly different interpretations, but generally there’s a consensus about the gist (e.g., it’s a greeting or a name). Many EVPs fall into this category.

- Class C EVP: Very low or unclear. You might sense voice-like cadence but cannot tell what is being said. One person might think it’s saying “John”, another thinks it’s a cough. Class C’s are often only recognized by the person who recorded them and often are not useful as evidence beyond personal intrigue (since they could be anything).

This class system, popularized by Sarah Estep among others, is subjective but helps investigators focus on the best evidence. As one paranormal researcher put it, Class A EVP depend on investigative rigor more than the others, because if you’re claiming to have something extraordinary (a clear ghost voice), you want to ensure you captured it under conditions that rule out trickery

pacificparanormal.com

. There’s an ethos element: you must persuade listeners to trust your Class A EVP is truly anomalous, which means you need to document how you got it and show you didn’t contaminate it.

When presenting evidence, many teams will only showcase Class As, maybe some really good Bs. The Class Cs and questionable stuff remain in the archives or “for fun” discussions. This practice is a form of self-verification: by holding a high bar for what you consider a solid EVP, you automatically filter out many false positives.

Analyzing Your Recording

We covered listening and enhancement in the How-To section, so here we’ll focus on specific analysis techniques and tools in a more technical sense:

- Critical Listening: This is the first and most important tool – your ears and brain, applied critically. Good analysts often log their thought process: e.g., “At 1:23, hear three syllables. Sounds like a child’s voice. Possibly saying ‘go away’? Need second opinion.” Being methodical and writing it down helps separate what’s actually there from what you think is there.

- Waveform and Spectral Analysis: Most audio software displays a waveform (amplitude over time). A sudden spike might reveal a loud event. But a spectrogram (frequency over time, usually with intensity shown by brightness or color) can be even more revealing. Human voices have a distinctive pattern of harmonics (formants). If you see such formant bands in a suspected EVP, it suggests a real vocalization occurred. If an “EVP” is actually just a scrape or a pop, the spectrogram will look different (maybe like a wide-band burst rather than harmonic lines). Some investigators use spectral analysis to differentiate EVPs from noise artifacts. Additionally, if you suspect a captured word might actually be a brief radio snippet, sometimes you’ll see a very narrow frequency band (like a carrier signal). True voices (human or presumably ghostly) usually spread across frequencies.

- Noise Reduction and Isolation: Carefully reducing hum or static can make a voice more audible. However, if you have to heavily process a clip to maybe hear a word, that EVP would likely be Class C at best, and you should note that. Still, noise reduction can clarify a Class B to approach Class A quality if done right. Another trick: frequency isolation – if you suspect the voice is mostly in, say, the 1000-3000 Hz band, you can filter out other frequencies to hear it more clearly. This sometimes makes a muffled voice pop out.

- Playback Speed Adjustment: Trying 0.8x or 1.2x speed might suddenly make gibberish intelligible. It’s possible a spirit voice doesn’t follow normal human timing (or it could be an echo of something played back at different speed). If you record at 44.1 kHz, try listening at 48 kHz and 32 kHz just to see if perception changes. Be careful not to trick yourself – always compare with original to ensure you’re not just convincing yourself because slower speech is easier to parse (our brain might fill more in when it has more time per syllable).

- Reverse Audio Check: Some investigators will listen to EVPs in reverse to ensure it’s not something like a phrase that makes more sense backwards (implying possibly an audio matrixing). This is not a common practice but worth mentioning – sometimes playing it backward can also solidify that it was just random noise (if backwards it sounds like the same kind of gibberish, then maybe forwards you were over-interpreting). It’s more a novelty analysis, though – EVPs are presumably forward-spoken unless you’re deep in the backmasking theory.

- Comparing Multiple Recorders: If you had more than one recorder running, check the same timestamp across them. If Recorder A got a whisper and Recorder B (across the room) got nothing at that moment, it suggests the sound was very localized (perhaps a real paranormal event focusing on one device, or perhaps just a mechanical noise of Recorder A). If both got it, compare volume levels: was it louder on one? That could indicate location of source. In an investigation of a supposed ghost voice on telephone recording, experts often check the other side’s recording if available to see if the voice is only on one side (which would be odd if it were just interference – interference might affect both).

- Duration and Formant Analysis: Human speech has certain patterns – vowels and consonants have typical durations. A trained ear or linguist might note, “That voice said a 5-syllable sentence in 1 second – that’s too fast for human speech.” Interestingly, some EVPs do seem sped up or slowed down relative to normal talk, which believers suggest might be due to time/dimensional differences. Skeptics say it’s because it’s not real speech, just noise that our brain is forcing into a speech rhythm (and it doesn’t perfectly match). If you find an EVP voice has very odd cadence (either too choppy or unnaturally monotone or whatnot), mark that. It doesn’t necessarily debunk it, but it’s an observation. Many EVPs indeed sound mechanical or odd in rhythm – not quite how a living person would speak. This could be a clue: either the method of production is different (if paranormal), or it’s just the brain trying to glue random bits together.